[Note: The following appeared, in slightly altered form, in a previous article, but I’ve added a new beginning.]

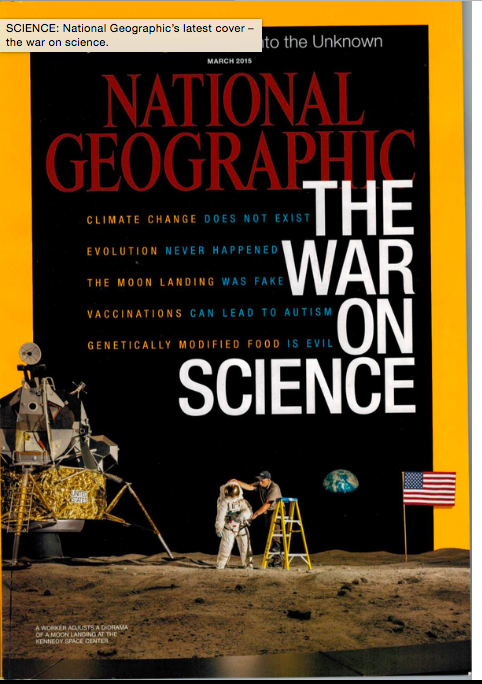

The only real way that knowledge and human progress can be derailed is by the systematic rejection of inductive reasoning, which forms the underpinnings not just of all science and the scientific-method, but of the entirety of human apprehension.

No scientist— whether researcher or practitioner or both, whether biologist, chemist, physicist, geologist, climate scientist, or any other —none can pursue knowledge without first having a view of what knowledge is and how that knowledge is acquired.

All scientists, therefore, whether they know it explicitly or not, need a theory of knowledge.

This theory must come from the most fundamental science: the science of philosophy.

The science of knowledge specifically belongs to that branch of philosophy called epistemology.

Epistemology?—?from the Greek word episteme, which means “knowledge”?—?is an extraordinarily complicated discipline that begins with three simple words: consciousness is awareness.

All scientists, I repeat, need a theory of knowledge, and this theory of knowledge subsequently affects every aspect of a scientist’s approach to her research?—?from the questions she asks, to the answers she found, to hypothesis and theories then developed and built-upon.

Very rare geniuses like Galileo and Newton and perhaps even Kepler (who, for all his mathematical brilliance and tireless work, held to a metaphysical viewpoint deeply flawed) were ferociously innovative in epistemology as well as physics —specifically, in systematizing and codifying the core principles of the inductive-method, which they all three came to through their scrupulous use of scientific experiment.

Induction more than anything else?—?including deduction?—?is the method of reason and the key to human progress.

A proper epistemology teaches a scientist, as it teaches everyone else concerned with comprehension and actual learning, how to exercise the full power of the human mind?—?which is to say, how to reach the widest abstractions while not losing sight of the specifics or, it you prefer, concretes.

A proper epistemolgy teaches how to integrate sensory data into a step-by-step pyramid of knowledge, culminating in the grasp of fundamental truths whose context applies to the whole universe. Galileo’s laws of motion and Newton’s laws of optics, as well as his laws of gravity, are examples of this. If humans were to one day transport to a sector of the universe where these laws did not hold true, it still wouldn’t invalidate them here. The context here remains. In this way, knowledge expands as context grow. The fact that all truths are by definition contextual does not invalidate absolute truth and knowledge thereby, but just the opposite: context is how we measure and validate truth.

Induction more than anything else — including deduction — is the method of reason and the key to human progress.

A proper epistemology teaches a scientist, as it teaches everyone else concerned with comprehension and actual learning, how to exercise the full power of the human mind — which is to say, how to reach the widest abstractions while not losing sight of the specifics, or concretes.

A proper epistemolgy teaches how to integrate sensory data into a step-by-step pyramid of knowledge, culminating in the grasp of fundamental truths whose context applies to the whole universe.

Epistemologically, postmodernism is the rejection of this entire process.

Postmodernism, in all its vicious variations, is a term devoid of any real content, and for this reason dictionaries and philosophy dictionaries offer very little help in defining it.

And yet postmodernism has today become almost universally embraced as the dominant philosophy of science — which is the primary reason that science crumbles before our eyes under its corrupt and carious epistemology.

Postmodernism, like everything else, is a philosophical issue. Accordingly, postmodernism’s tentacles have extended into every major branch of philosophy — from metaphysics, to epistemology, to esthetics, to ethics, to politics, to economics.

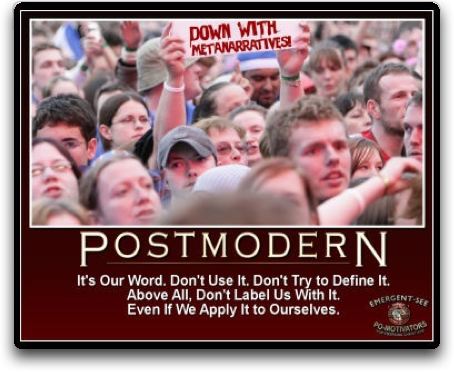

In order to get any kind of grasp on postmodernism, one must grasp first that postmodernism doesn’t want to be defined. Its distinguishing characteristic is in the dispensing of all definitions — because definitions presuppose a firm and comprehensible universe. Accurate definitions are guardians of the human mind against the chaos of psychological disintegration.

You must understand next that postmodernism is a revolt against the philosophical movement that immediately preceded it: Modernism.

We’re told by postmodernists today, that modernism and everything that modernism stands for is dead.

Thus, whereas modernism preached the existence of independent reality, postmodernism preaches anti-realism, solipsism, and “reality” as a term that always requires quotation marks.

Whereas modernism preached reason and science, postmodernism preaches social subjectivism and knowledge by consensus.

Whereas modernism preached free-will and self-governance, postmodernism preaches determinism and the rule of the collective.

Whereas modernism preached the freedom of each and every individual, postmodernism preaches multiculturalism, environmentalism, egalitarianism by coercion, social-justice.

Whereas modernism preached free-markets and free-exchange, postmodernism preaches Marxism and its little bitch: statism.

Whereas modernism preached objective meaning and knowledge, postmodernism preaches deconstruction and no-knowledge — or, if there is any meaning at all (and there’s not), it’s subjective and ultimately unverifiable.

In the words of one of postmodernism’s high priests, Michel Foucault: “It is meaningless to speak in the name of — or against — Reason, Truth, or Knowledge.”

Why?

Because according to Mr. Foucault again: “Reason is the ultimate language of madness.”

We can thus define postmodernism as follows:

It is the philosophy of absolute agnosticism —agnosticism in the literal sense of the word — meaning: a philosophy that preaches the impossibility of human knowledge.

What this translates to in day-to-day life is pure subjectivism, the ramifications of which are, in the area of literature, for example, no meaning, completely open interpretation, unintelligibility.

Othello, therefore, is as much about racism and affirmative-action as it is about jealousy.

Since there is no objective meaning in art, all interpretations are equally valid.

Postmodernism is anti-reason, anti-logic, anti-intelligibility.

Politically, it is anti-freedom. It explicitly advocates leftist, collectivist neo-Marxism and the deconstruction of industry, as well as the dispensing of inalienable rights to property and person.

There is, however, a profound and fatal flaw built into the very premise of postmodernism, which flaw makes postmodernism impossible to take seriously and very easy to reject:

If reason and logic are invalid and no objective knowledge is possible, then the whole pseudo-philosophy of postmodernism is also invalidated.

One can’t use reason and the reasoning process, even in a flawed form, to prove that reason is false.