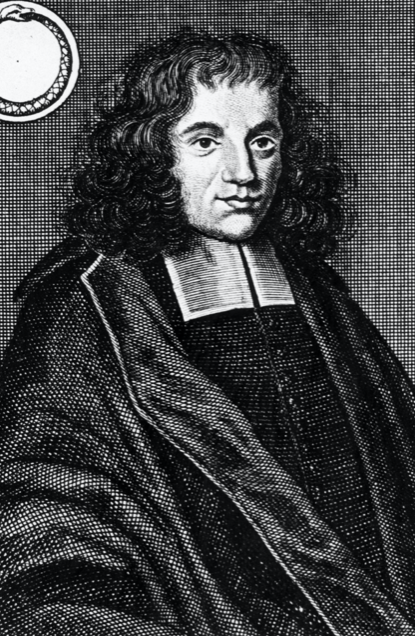

[If this subject-matter appeals to you, this might as well. Spinoza was an inspiration.]

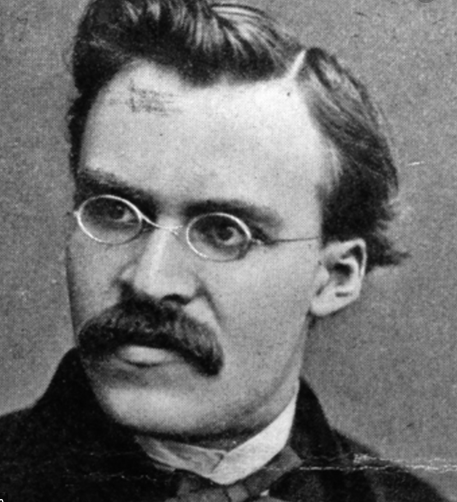

Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) and Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) are two of the most radical thinkers of all time.

They don’t have everything in common — though they’re not totally dissimilar either—and yet if there’s one thing they do both possess, it’s this: an unsettling power to obliterate preconceived notions and unquestioned dogmas — the safe, secure beliefs that most humans hold.

Nietzsche, who’s fairly well-known, is the philosopher you can never quite dismiss — no matter how much you might wish to dismiss him. Over a century after his death, Nietzsche still has an almost uncanny ability to turn a worldview upside-down, with the abruptness of a bone-snap, via a single bludgeoning remark.

Baruch Spinoza, upon the other hand (Baruch is Dutch for “Benito,” from the Latin “Benedict,” meaning “blessed”), isn’t nearly as well-known. Yet at his best, he’s every bit as heterodox and as fulguratingly brilliant as Nietzsche, with an equal or even superior power to slash entire belief-systems in one fell guillotine-swoop.

This is the total testament to the power of ideas.

Upon his first reading of Spinoza, Nietzsche wrote:

“I am utterly amazed, utterly enchanted! I have a precursor, and what a precursor! I hardly knew Spinoza: that I should have turned to him just now, was inspired by ‘instinct.’ Not only is his over-tendency like min — namely to make all knowledge the most powerful affect — but in five main points of his doctrine I recognize myself. This most unusual and loneliest thinker is closest to me precisely in these matters.”

Even today, the words of both men still contain enough live-wire voltage to electrify every bodily nerve. Their ideas — as wildly controversial now as they ever were — are unequivocally at odds with the status-quo.

Off-the-mark or on it, both men were incontrovertibly freethinkers, in the purest sense of the word, and this is no small thing: the independent mind, with the strength and confidence to think for itself, is always a virtue.

Thus, however you ultimately regard either of them, please pay respect to their independence of thought, which, in any place or era, requires a great act of courage — courage continually exerted — because the colossal ocean of conformity and the cult-like mentality of the mob threatens forever to drown out the one who would dare think for herself.

Here are 101 unapologetic, unsympathetic remarks from the men themselves. Some of these remarks you will perhaps agree with. Others you will perhaps resist. Pay closest attention to the latter — because these are almost certainly the ones which most challenge your own:

The superstitious know how to reproach people for their vices better than they know how to teach them virtues, and they strive not to guide people by reason, but to restrain them by fear; so that they flee the evil rather than love virtues. Such people aim only to make others as wretched as they themselves are, so it is no wonder that they are generally burdensome and hateful to the rest of humanity. — Spinoza

Superstition is founded on ignorance. — Spinoza

Everyone by a supreme law of nature is master of his own thoughts. — Spinoza

If you want the present to be different from the past, study the past. — Spinoza

Peace is not the absence of war, but rather a virtue that springs from a state of mind: a disposition for benevolence, confidence, justice. — Spinoza

All happiness or unhappiness solely depends upon the quality of the object to which we are attached by love. — Spinoza

I do not attribute to nature either beauty or deformity, order or confusion; because it is only in relation to the human mind and our imaginations that things can be called beautiful or ugly, well-ordered or confused. — Spinoza

The highest activity a human being can attain is learning for understanding, because to understand is to be free. — Spinoza

I have made a ceaseless effort not to ridicule, not to bewail, not to scorn human actions, but to understand them. — Spinoza

Apply yourself with real energy to serious work. — Spinoza

I call him free who is led solely by reason. — Spinoza

Everything excellent is as difficult as it is rare. — Spinoza

Will and intellect are one and the same thing. — Spinoza

The less the mind understands and the more things it perceives, the greater its power of feigning is; and the more things it understands, the more that power is diminished. — Spinoza

Don’t cry and don’t rage. Understand. — Spinoza

The vain and vainglorious love the company of parasites or flatterers and hate the company of those of noble spirit. — Spinoza

Rarely do people live by the guidance of reason but instead are generally disposed to envy and disdain. — Spinoza

Knowledge of evil is inadequate knowledge, without a counter knowledge of the good. — Spinoza

The real slave lives under the sway of pleasure and can neither see nor do what is for their own good. — Spinoza

Vice will exist so long as people exist. — Spinoza

We are so constituted by nature that we are ready to believe what we hope and reluctant to believe what we fear. — Spinoza

Reason alone asserts its claim to the realm of truth. — Spinoza

Reason is a faculty for the integration of knowledge that human beings possess. — Spinoza

Truth is the apprehension of reality. — Spinoza

Truth more than anything else has the power to effect a close union between different sentiments and dispositions. — Spinoza

People under the guidance of reason seek nothing for themselves that they would not desire for the rest of humanity. — Spinoza

I am at a loss to understand the reasoning whereby it is considered that chance and necessity are not contraries. — Spinoza

A thing does not cease to be true merely because it is not accepted by many. — Spinoza

The investigation of Nature in general is philosophy. — Spinoza

In demonstrating the truths of Nature, does not truth reveal its own self? — Spinoza

Reason is in reality the light of the mind, without which the mind sees nothing but dreams and fantasies. — Spinoza

Truth becomes a casualty when in trials attention is paid not to justice or truth but to the extent of anything other. — Spinoza

Freedom is of the first importance in fostering the sciences and the arts.– Spinoza

Everywhere truth becomes a casualty through hostility or servility when despotic power is in the hands of one or few. — Spinoza

Emotional distress and unhappiness have their origin mostly in excessive love toward a thing which is subject to considerable instability. — Spinoza

Healthy people take solitary tranquil pleasure in existence and thus enjoy a better life than those who live merely to avoid death. — Spinoza

When one is prey to her emotions, she is not her own master. — Spinoza

The endeavor to understand is the first and only basis of virtue. — Spinoza

He alone is free who lives with free consent under the entire guidance of reason. — Spinoza

The effort to make everyone else approve what we love or hate is, in truth, a kind of warped ambition, and so we see that each person by nature desires that other persons should live according to his way of thinking. — Spinoza

The wise are richest in not greedily pursuing riches at the expense of everything else. — Spinoza

If we could live by reason as much as we are led by blind desire, all would order their lives wisely in being by reason led. — Spinoza

Evil is that which hinders a person’s capacity to perfect reason and to enjoy a rational life. — Spinoza

People possess nothing more excellent than understanding, and can suffer no greater punishment than their folly. — Spinoza

The majority of people are quite incapable of distracting their minds from thinking upon any other goods besides sensual pleasure or riches. — Spinoza

Desires and aims that arises from reason cannot be excessive.– Spinoza

The more clearly you understand yourself and your emotions, the more you become a lover of what is. — Spinoza

Those who know the true use of money, and regulate the measure of wealth according to their needs, live contented. — Spinoza

Don’t be astonished at new ideas — for it’s well known that a thing doesn’t cease to be true merely because it’s not accepted by many. — Spinoza

Insofar as the mind sees things in their eternal aspect, it participates in eternity. — Spinoza

Happiness is not the reward of virtue, but is virtue itself. — Spinoza

Nor do we delight in happiness because we restrain from our lusts, but on the contrary, because we delight in it, we are therefore able to restrain them. — Spinoza

Excessive pride, or self-abasement, indicates excessive weakness of spirit. — Spinoza

Hatred is increased by being reciprocated, yet can on the other hand be destroyed by love. — Spinoza

Hatred which is completely vanquished by love, passes into love, and love is thereupon greater than if hatred had not preceded it. — Spinoza

Minds are conquered not by arms, but by love and nobility. — Spinoza

Self-preservation is the fundamental foundation of virtue. — Spinoza

Ignorance of truth and true-causes makes for total confusion. — Spinoza

Conduct that brings about harmony is that which is related to justice and equity. — Spinoza

The better part of us is in harmony with the order of the whole of Nature. — Spinoza

All happiness or unhappiness solely depends upon the quality of the object to which we are attached by love. — Spinoza

Love is nothing but Joy with the accompanying idea of an external cause. — Spinoza

Love agrees with reason if its cause is not merely physical beauty but especially freedom of the spirit. — Spinoza

Devotion is love toward one at whom we wonder. — Spinoza

Most people parade their own ideas as God’s word, mainly to compel others to think like them under religious pretexts. — Spinoza

The mind of God is all the mentality that is scattered over space and time, the diffused consciousness that animates the world. — Spinoza

Outside Nature, there is and can be no thing and no being. — Spinoza

A miracle — either contrary to Nature or above Nature — is mere absurdity. — Spinoza

Nothing exists from whose nature an effect does not follow. — Spinoza

Everyone should be allowed freedom of judgment and the right to interpret the basic tenets of their faith as they and they alone think fit. — Spinoza

The eternal part of the mind is the intellect, through which alone we are said to be active. — Spinoza

I do not know how to teach philosophy without becoming a disturber of the peace. — Spinoza

Only free people are truly grateful to one another. — Spinoza

The supreme mystery of despotism, its prop and stay, is to keep men in a state of deception, and with the specious title of religion to cloak the fear by which they must be held in check, so that they will fight for their servitude as if for salvation. — Spinoza

When all decisions are made by a few people who have only themselves to please, freedom and the common good are lost. — Spinoza

The mind is passive only to the extent that it has inadequate or confused ideas. — Spinoza

The ultimate aim of just government is not to rule, or restrain by fear, nor to exact obedience, but to free every man from fear that he may live in all possible security. In fact the true aim of government is liberty. — Spinoza

All laws which can be violated without doing any one any injury are laughed at. — Spinoza

He who tries to determine everything by law will foment crime rather than lessen it. — Spinoza

Those who take an oath by law will avoid perjury more if they swear by the welfare & freedom of the state instead of by God. — Spinoza

A society will be more secure, stable & less exposed to fortune, which is founded & governed mainly by people of wisdom. — Spinoza

Those who cannot manage themselves and their private affairs will far less be capable of caring for the public interest. — Spinoza

In adversity, there is no counsel so foolish, absurd, or vain which people will not follow. — Spinoza

An entire people will never transfer its rights to a few people or to one person if they can reach agreement among themselves. — Spinoza

I counsel you, my friends: Distrust all in whom the impulse to punish is powerful. — Nietzsche

We often refuse to accept an idea merely because the way in which it has been expressed is unsympathetic to us. — Nietzsche

The surest way to corrupt a youth is to instruct him to hold in higher esteem those who think alike than those who think differently. — Nietzsche

God is a thought who makes crooked all that is straight. — Nietzsche

When a hundred humans stand together, each of them loses their minds and gets another one. — Nietzsche

Nothing on earth consumes a man more quickly than the passion of resentment. — Nietzsche

A politician divides mankind into two classes: tools and enemies .– Nietzsche

The state is the coldest of all cold monsters who bites with stolen teeth. — Nietzsche.

Everyone who has ever built anywhere a new heaven first found the power thereto in his own hell. — Nietzsche

There is more wisdom in your body than in your deepest philosophy. –Nietzsche

The Kingdom of Heaven is a condition of the heart — not something that comes upon the earth or after death. — Nietzsche

In large states public education will always be mediocre, for the same reason that in large kitchens the cooking is usually bad. — Nietzsche

A casual stroll through the lunatic asylum shows that faith does not prove anything. — Nietzsche

No victor believes in chance. — Nietzsche

Convictions are more dangerous foes of truth than lies. — Nietzsche

Talking much about oneself can also be a means to conceal oneself. — Nietzsche

It is not a lack of love, but a lack of friendship that makes unhappy marriages. — Nietzsche

The essence of all beautiful art, all great art, is gratitude. — Nietzsche

Rejoicing in our joy, not suffering over our suffering, is what makes someone a friend. — Nietzsche

The most common lie is that which one tells himself; lying to others is relatively an exception. — Nietzsche