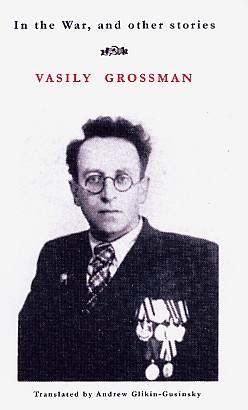

Howard Zinn was born on August 24, 1922. He died January 27, 2010.

Howard Zinn was born on August 24, 1922. He died January 27, 2010.

Zinn taught Political Science at Boston University from 1964 until 1988; he was an American historian, of sorts, a self-proclaimed Marxist who, by his own admission, did not believe in objective history:

I wanted my writing of history and my teaching of history to be a part of social struggle. I wanted to be a part of history and not just a recorder and teacher of history. So that kind of attitude towards history, history itself as a political act, has always informed my writing and my teaching….

Objectivity is impossible, and it is also undesirable. That is, if it were possible it would be undesirable, because if you have any kind of a social aim, if you think history should serve society in some way; should serve the progress of the human race; should serve justice in some way, then it requires that you make your selection on the basis of what you think will advance causes of humanity.

Howard Zinn is probably second only to Noam Chomsky in terms of the neo-Marxist influence he wields, and in light of Howard Zinn’s recent revivification, which began just prior to his death, the History Channel aired a program called The People Speak, which was a documentary written and produced by Matt Damon and based upon Howard Zinn’s propaganda publication A People’s History of the United States.

Quoting from his People’s History:

“The American system is the most ingenious system of control in world history, because it uses wealth to turn those in the 99 percent against one another” (A People’s History of the United States, Howard Zinn).

That is Howard Zinn’s philosophy in compendiated form: Ninety-nine out of one hundred of us are not actually free, even if we think we are, because income inequalities exist.

Howard Zinn never seriously asked why income inequalities exist in the first place — at least, not that I’ve ever seen — but the answer to that question is this: not everyone possesses the same degree of talent, skill, and most especially, ambition. (This point, incidentally, was dramatized persuasively in the late Kurt Vonnegut’s short story “Harrison Bergeron.”)

Inequality is inherent to freedom.

Humans left free naturally stratify, as several famous experiments have demonstrated. Why? Because of the reason just stated: humans possess varying degrees of talent, brains, and most of all, ambition.

Freedom, of course, does not guarantee wealth; it does not guarantee success. Freedom is one thing and one thing only: the absence of compulsion. It simply means that you are left alone. Freedom means no entitlements, no minimum guarantees, no help (or hindrance) at all, no public education, no free health care, no drinking laws, no illegalization of drugs, and so on.

Howard Zinn did not pretend to be an advocate of liberty. He, like all postmodernists and neo-Marxists, believed that “social equality” and “social justice” are more important than freedom, and, accordingly, individual rights (particularly the inalienable right to your own property — i.e. your money) can be lawfully expropriated by the government and redistributed.

To this day, Zinn’s A People’s History remains a staple among academics and other leftists — despite the fact that it is the only “academic” history book that doesn’t contain a single source citation, and despite the fact that it was refuted long ago, and devastatingly so, by the Harvard historian Oscar Handlin in the pages of the The American Scholar (49). Here’s an excerpt of that refutation:

It simply is not true that ‘what Columbus did to the Arawaks of the Bahamas, Cortez did to the Aztecs of Mexico, Pizarro to the Incas of Peru, and the English settlers of Virginia and Massachusetts to the Powhatans and the Pequots.’ It simply is not true that the farmers of the Chesapeake colonies in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries avidly desired the importation of black slaves, or that the gap between rich and poor widened in the eighteenth-century colonies. Zinn gulps down as literally true the proven hoax of Polly Baker and the improbable Plough Jogger, and he repeats uncritically the old charge that President Lincoln altered his views to suit his audience. The Geneva assembly of 1954 did not agree on elections in a unified Vietnam; that was simply the hope expressed by the British chairman when the parties concerned could not agree. The United States did not back Batista in 1959; it had ended aid to Cuba and washed its hands of him well before then. ‘Tet’ was not evidence of the unpopularity of the Saigon government, but a resounding rejection of the northern invaders (Dr. Oscar Handlin, The American Scholar, 49, 1980).

Ron Radosh has also very recently written an excellent article on Mr. Howard Zinn and Mr. Good Will Hunting.

Howard Zinn: 1922-2010