Venezuelan supermarket:

It was in early autumn of 1989 that the drunkard Boris Yeltsin, soon-to-be president of the Soviet Union, visited, for the first time in his life, a supermarket in Houston, Texas.

Not long afterward, in his autobiography Against the Grain, Yeltsin wrote about this watershed moment:

“When I saw those shelves crammed with hundreds, thousands of cans, cartons and goods of every possible sort, I felt quite frankly sick with despair for the Soviet people.”

Michael Dobbs, describing that same moment in his book Down With Big Brother: The Fall of the Soviet Empire, said this:

A turning point in Yeltsin’s intellectual development occurred during his first visit to the United States in September 1989, more specifically his first visit to an American supermarket, in Houston, Texas. The sight of aisle after aisle of shelves neatly stacked with every conceivable type of foodstuff and household item, each in a dozen varieties, both amazed and depressed him. For Yeltsin, like many other first-time Russian visitors to America, this was infinitely more impressive than tourist attractions like the Statue of Liberty and the Lincoln Memorial. It was impressive precisely because of its ordinariness. A cornucopia of consumer goods beyond the imagination of most Soviets was within the reach of ordinary citizens without standing in line for hours. And it was all so attractively displayed. For someone brought up in the drab conditions of communism, even a member of the relatively privileged elite, a visit to a Western supermarket involved a full-scale assault on the senses.

“What we saw in that supermarket was no less amazing than America itself,” recalled Lev Sukhanov, who accompanied Yeltsin on his trip to the United States and shared his sense of shock and dismay at the gap in living standards between the two superpowers. “I think it is quite likely that the last prop of Yeltsin’s Bolshevik consciousness finally collapsed after Houston. His decision to leave theparty and join the struggle for supreme power in Russia may have ripened irrevocably at that moment of mental confusion.”

On the plane, traveling from Houston to Miami, Yeltsin seemed lost in his thoughts for a long time. He clutched his head in his hands. Eventually he broke his silence. “They had to fool the people,” he told Sukhanov. “It is now clear why they made it so difficult for the average Soviet citizen to go abroad. They were afraid that people’s eyes would open.”

Many years before, when Nikita Kruschev first visited the United States, he, too, was taken to a garden-variety supermarket. And what he saw there looked to him so beyond belief that he actually thought it was all set up to deceive him. Poverty and want had been so thoroughly inculcated into him that he simply couldn’t accept that Kapitalist America had such a rich variety of food and household goods readily available for everyone, twenty-four hours a day, everyday.

Venezuela, as you know, has been under socialist rule for decades, regime after regime militantly opposed to free-markets, and I’d like the stark contrast to serve as a reminder to those who support government control of healthcare, as against free-market medicine — free-market medicine, mind you, which I’ve always said will provide far greater goods and services, at higher quality and lower costs, than any government committee, no matter how ingenious, could ever in its wildest imagination conceive.

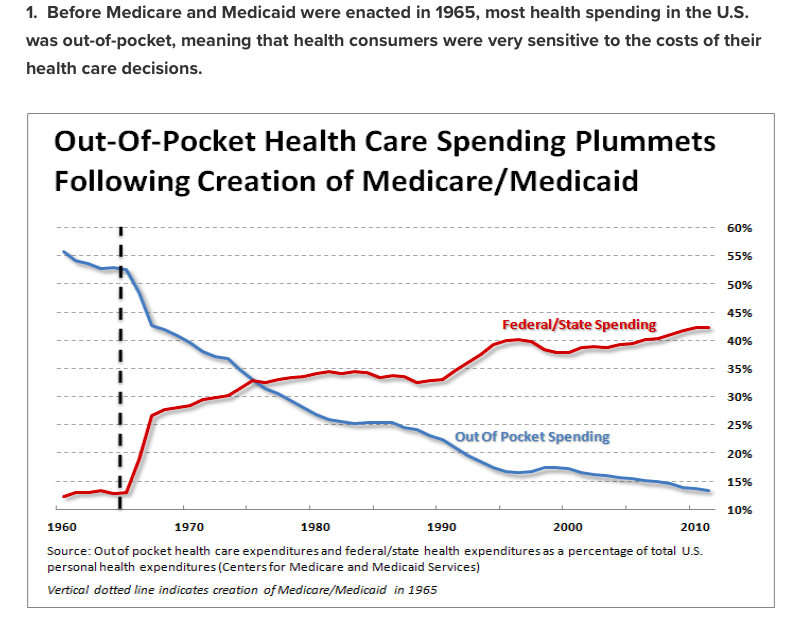

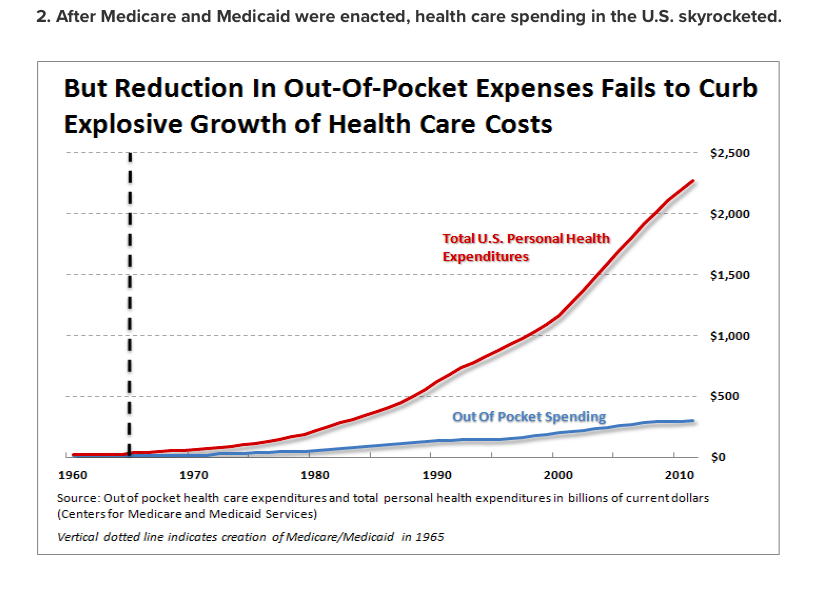

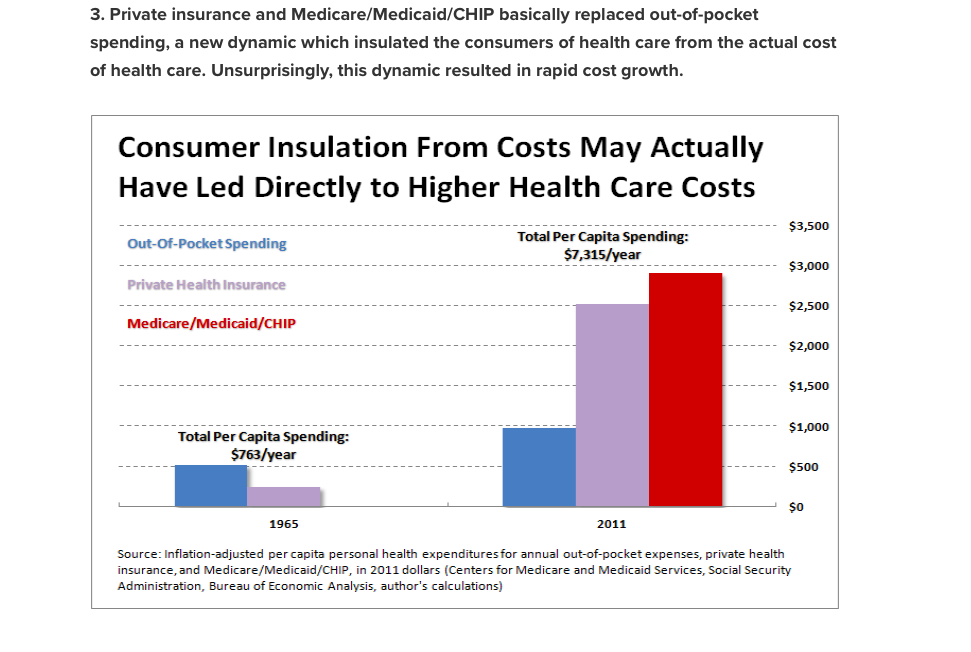

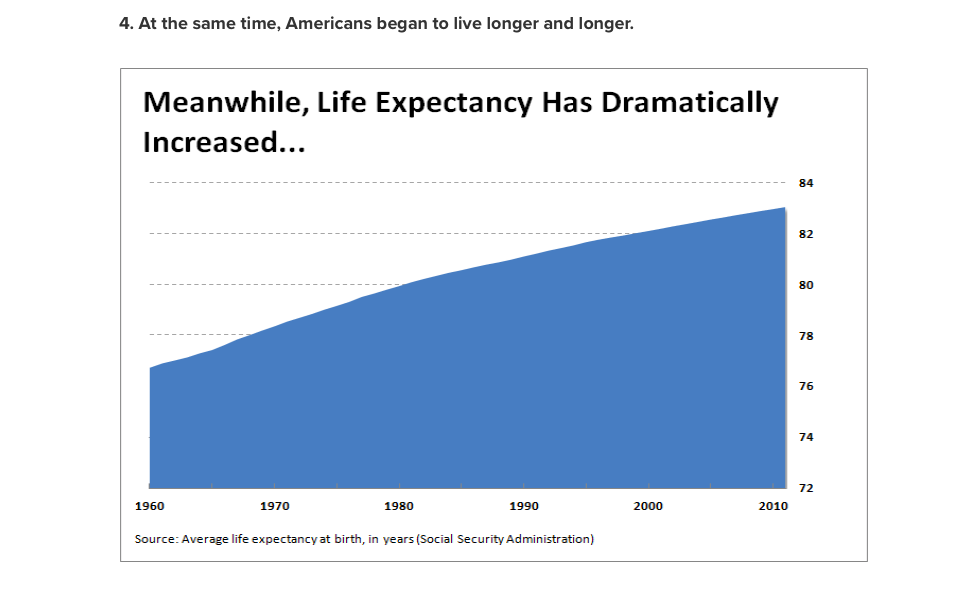

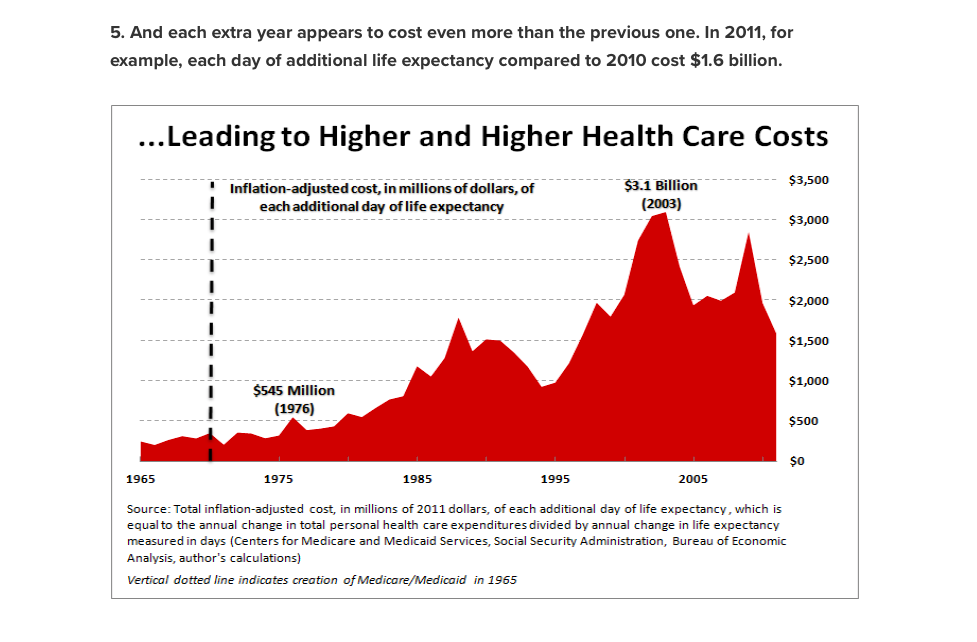

Here are five charts which show the very clear progression and correlation of rising healthcare costs and socialized medicine in America: