Sometimes you have to see it to believe it.

Sometimes you have to see it to believe it.

The following Op-Ed, which appeared in yesterday’s New York Times, was written by one Daniel E. Lieberman, a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard — a fact I mention only because you, like me, might be tempted to think that someone with those sort of Ivy League credentials wouldn’t be capable of something so misbegotten. But you and I would both be wrong.

It just goes to show: the human capacity for rationalization is limitless. In this case, what’s being rationalized is the leftist justification of government force.

Here’s an excerpt:

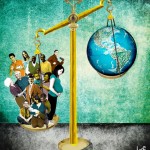

OF all the indignant responses to Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg’s plan to ban the sale of giant servings of soft drinks in New York City, libertarian objections seem the most worthy of serious attention. People have certain rights, this argument goes, including the right to drink lots of soda, to eat junk food, to gain weight and to avoid exercise. If Mr. Bloomberg can ban the sale of sugar-laden soda of more than 16 ounces, will he next ban triple scoops of ice cream and large portions of French fries and limit sales of Big Macs to one per order? Why not ban obesity itself?

The obesity epidemic has many dimensions, but at heart it’s a biological problem. An evolutionary perspective helps explain why two-thirds of American adults are overweight or obese, and what to do about it. Lessons from evolutionary biology support the mayor’s plan: when it comes to limiting sugar in our food, some kinds of coercive action are not only necessary but also consistent with how we used to live.

Read the full article here.