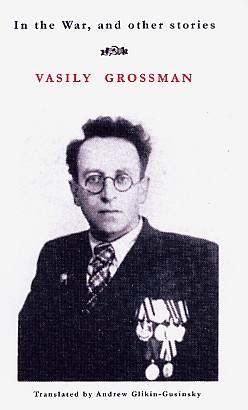

The Russian writer Vasily Grossman was born in 1905 in what is now the Ukrainian town of Berdichev. At that time, Berdichev was still part of the Russian Empire. Vasily Grossman attended high school in Kiev and then the University of Moscow. He graduated from University in 1929 with a degree in chemical engineering. He worked as an engineer for five years, after which time he devoted himself entirely to writing.

He published his first news article in 1928, his first fictional story in 1934.

During the middle and latter 1930’s Vasily Grossman was exceptionally prolific, and even more so after the start of World War II. At that point he became a correspondent for Red Star (Krasnaya Zvezda). He spent the entire war on the treacherous front, covering, in minute detail, the blood-soaked siege of Stalingrad. In popularity his war reportage was second to none (well, maybe one: the famous Ehrenburg), and Grossman is loosely portrayed by actor Joseph Fiennes in the inaccurate movie Enemy at the Gates.

In his youth and well into his thirties, Vasily Grossman was devoted to the communist philosophy. But during and immediately after the war, he became increasingly disillusioned with that socialist system, so that, starting in 1943, he began explicitly challenging the whole Soviet ideal — both for its repression of freedom and for its anti-Semitism.

His war fiction at this time also began to generate criticism from high Soviet officials. In a matter of months, thus, his writings were suppressed. Over the course of his latter years, Vasily Grossman became an outright opponent of socialism. His writings are, at times, not consistently, among the most eloquent expression of freedom of any person in any era.

Stomach cancer killed him in 1964.

What follows is a short passage from his last novel Forever Flowing. It is one side of a brief dialogue spoken, in part, by the novel’s protagonist Ivan Grigoryevich, who after thirty years of imprisonment has just been released from the Russian Gulag. I quote it as a tribute to freedom, to be sure, but also as a tribute to the man who came to understand the philosophical roots of freedom — and that in a country where freedom was not allowed; in a country where philosophies and freedom were replaced by blind obedience and dogma. It’s important that people like Vasily Grossman are not forgotten.

I’d like you to please think of the following passage the next time you hear, for example, an environmentalist talk about more centralized government and more government ownership of land for the sake of “our endangered environment.”

Please think of it next time you see someone wearing a Che Guevara T-shirt (or necklace) in glorification of Che Guevara’s communistic ideals, or romanticizing communist Cuba and Castro for their healthcare system, or Chairman Mao with the blood of billions on his hands:

I used to think freedom was freedom of speech, freedom of press, freedom of conscience. But freedom is the whole life of everyone. Here is what it amounts to: you have to have the right to sow what you wish to, to make shoes or coats, to bake into bread the flour ground from the grain you have sown, and to sell it or not sell it as you wish; for the lathe operator, the steelworker, and the artist it’s a matter of being able to live as you wish and work as you wish and not as they order you to. And in our country there is no freedom – not for those who write books nor for those who sow grain nor for those who make shoes.

Forever Flowing

Vasily Grossman (1905–1964)