A few weeks ago, I posted an article entitled Eleven Facts About the Minimum Wage Barack Obama Forgot to Mention, which I found on a website called The Federalist, and which was written by a man named Sean Davis, about whom I know next to nothing.

I liked his article, however, and I was surprised at some of the responses I got from readers who are also customers at my work.

The whole idea of a minimum wage is dangerously flawed, and here’s the essence of why:

There’s really no question that the only thing which can ultimately raise wages for workers is improvements in technology, which in turn increase productivity, which in turn increases capital.

As the great Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises explained it:

The technological improvement in the production of A makes it possible to realize certain projects which could not be executed before because the workers required were employed for the production of A for which consumers’ demand was more urgent. The reduction of the number of workers in the A industry is caused by the increased demand of these other branches to which the opportunity to expand is offered. Incidentally, this insight explodes all talk about “technological unemployment.”

Tools and machinery are primarily not labor-saving devices, but means to increase output per unit of input. They appear as laborsaving devices if looked upon exclusively from the point of view of the individual branch of business concerned. Seen from the point of view of the consumers and the whole of society, they appear as instruments that raise the productivity of human effort. They increase supply and make it possible to consume more material goods and to enjoy more leisure. Which goods will be consumed in greater quantity and to what extent people will prefer to enjoy more leisure depends on people’s value judgments.

All that minimum wage rates can accomplish with regard to the employment of machinery is to shift additional investment from one branch into another. Let us assume that in an economically backward country, Ruritania, the stevedores’ union succeeds in forcing the entrepreneurs to pay wage rates which are comparatively much higher than those paid in the rest of the country’s industries. Then it may result that the most profitable employment for additional capital is to utilize mechanical devices in the loading and unloading of ships. But the capital thus employed is withheld from other branches of Ruritania’s business in which, in the absence of the union’s policy, it would have been employed in a more profitable way. The effect of the high wages of the stevedores is not an increase, but a drop in Ruritania’s total production.

Real wage rates can rise only to the extent that, other things being equal, capital becomes more plentiful. If the government or the unions succeed in enforcing wage rates which are higher than those the unhampered labor market would have determined, the supply of labor exceeds the demand for labor. Institutional unemployment emerges (Ludwig von Mises, Human Action, Chapter 30).

(If you don’t want to read all that, just read the last paragraph.)

A few days ago, more than 500 economists, three Nobel laureates among them (Vernon Smith, Eugene Fama and Ed Prescott) signed this letter arguing that “artificially raising the minimum wage to $10.10 per hour through a government mandate would have adverse effects on the employment opportunities for unskilled and low-skilled workers. The tragedy of this well-intentioned, but misguided legislation is that it would harm and disadvantage the very workers it is intended to help.”

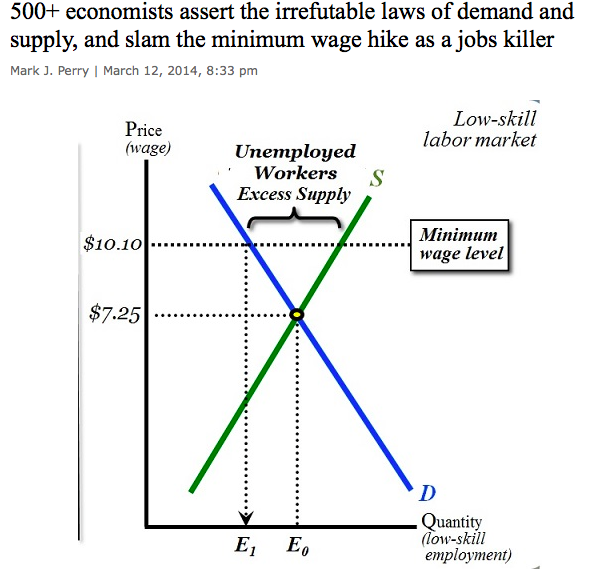

In voicing their collective objection to a government price control for entry-level workers, the 500+ economists asserted the Law of Demand and the Law of Supply, two fundamental and time-tested components of basic economy price theory, summarized graphically above. Following a 40% increase in the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to $10.10 per hour, we would expect two incontrovertible effects: a) the number of unskilled, low-skilled and entry-level workers hired by employers would decrease (a movement upward to the left from $7.25 per hour along the blue demand curve above), and b) the number of unskilled and low-skilled workers looking for entry-level jobs would increase (a movement upward to the right from $7.25 per hour) along the green supply curve above). In combination, those two perfectly predictable and unavoidable effects inevitably leads to an “excess supply of unskilled workers” in the graph above, which is just another term for “more unemployed unskilled workers,” and a higher jobless rate for those workers.

Bottom Line: No amount of wishful thinking or well-intentioned legislation will change the unavoidable outcome of reduced employment opportunities for entry-level workers in America illustrated graphically above. The 500+ economists who have signed the letter are in general agreement that economic reality and the laws of supply and demand are not optional, despite the arrogant attempts of economically-challenged politicians and progressives to circumvent or disregard the most basic economic theory, economic laws and economic logic.

(Link)