In the Concise Guide To Economics, author and economist Jim Cox correctly explains that the Multiplier is one of the major components of Keynesian policy.

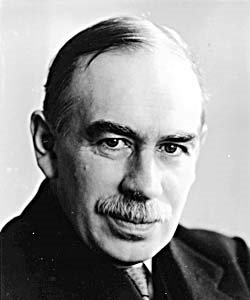

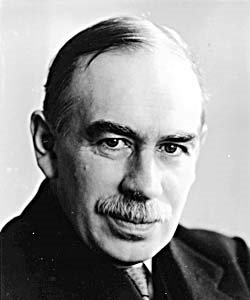

For those who still don’t know it, Keynesian economics — named after John Maynard Keynes — are the economics that Barack Obama, as well as George W. Bush (et al), espouse in full.

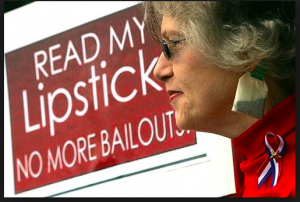

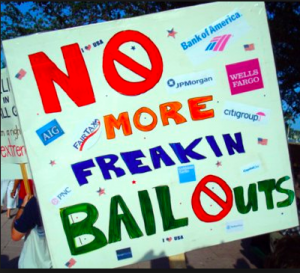

The following explanation of the Multiplier Theory, though exceptionally clear and cogent, gets a bit technical, but please read through it. It is short, and it is also crucial that everyone understands the degree to which economic illiteracy grips the political leaders who have power over us.

The multiplier effect can be defined as the greater resulting income generated from an initial increase in spending. (For example, an increase in spending of $100 will generate a total increase in income received of $500 as the initial income is respent by each succeeding recipient–these figures are based on an assumption that each income receiver spends 80% of his additional income and saves 20%, the formula being Multiplier = 1 / % Change in Saving.)

Fundamentally, the multiplier is theory run amok, as Henry Hazlitt has explained in The Failure of the New Economics:

If a community’s income, by definition, is equal to what it consumes plus what it invests, and if that community spends nine-tenths of its income on consumption and invests one-tenth, then its income must be ten times as great as its investment. If it spends nineteen-twentieths on consumption and invests one-twentieth, then its income must be twenty times as great as its investment….And so ad infinitum. These things are true simply because they are different ways of saying the same thing. The ordinary man in the street would understand this. But suppose you have a subtle man, trained in mathematics. He will then see that, given the fraction of the community’s income that goes into investment, the income itself can mathematically be called a “function” of that fraction. If investment is one-tenth of income, income will be ten times investment, etc. Then, by some wild leap, this “functional” and purely formal or terminological relationship is confused with a causal relationship. Next the causal relationship is stood on its head and the amazing conclusion emerges that the greater the proportion of income spent, and the smaller the fraction that represents investment, the more this investment must “multiply” itself to create the total income! p. 139

A bizarre but necessary implication of this theory is that a community which spends 100% of its income (and thus saves 0%) will have an infinite increase in its income–sure beats working!

A further reductio ad absurdum is provided by Hazlitt:

Let Y equal the income of the whole community. Let R equal your (the reader’s) income. Let V equal the income of everybody else. Then we find that V is a completely stable function of Y; whereas your income is the active, volatile, uncertain element in social income. Let us say the income arrived at is:

V = .99999 Y

Then, Y = .99999 Y + R

.00001 Y = R

Y = 100,000 R

Thus we see that your own personal multiplier is far more powerful than the investment multiplier, it is only necessary for the government to print a certain number of dollars and give them to you. Your spending will prime the pump for an increase in the national income 100,000 times as great as the amount of your spending itself. pp. 150 -151

The multiplier is based on a faulty theory of causation and is therefore in actuality nonexistent. Keynesians today will often admit to this but cling to their multiplier by citing the fact that it has a regional effect. Without them saying so explicitly, what this means is that if income is taken from citizens of Georgia and spent in Massachusetts it will benefit the Massachusetts economy(!).

The multiplier is an elaborate attempt to obfuscate the issues to excuse government spending. It and Keynesian theory are nothing more than an elaborate version of any monetary crank’s call for inflation; Keynes managed to dredge up the fallacies of the 17th century’s mercantilist views only to relabel them as the “new economics”!

(Link)