Communism is a species of the genus socialism. It is one of the many variations on the theme.

Communism explicitly calls for the violent overthrow of government. In theory, it is an anarchist ideology which believes that the state will one day magically “wither away,” as Karl Marx famously phrased it, though only after an unspecified period of GIGANTIC bureaucratic control. Of course, in the long and blood-soaked history of communism, the state has never withered away, and never will. Why? Once entrenched, bureaucracy is impossible to retrogress away from.

Democratic socialism, on the other hand, doesn’t advocate the violent overthrow of government but intends to use force peacefully. By definition, by its very nature, socialism must resort to force because it must expropriate people’s money and other property in order to redistribute it. That is the distinguishing characteristic of any and all forms of socialism: government control of property and the means of production (which is one of the reasons “corporatism” — i.e. crony capitalism — is another variation on socialism).

One must never forget: socialism is by definition an ideology of force.

Not all liberals are, strictly speaking, socialists — in large part because most of them don’t even really know what “socialism” means, and it is for this reason also that many liberals, and, for that matter, many conservatives, are socialists and do not even know it.

Welfare statism is not exactly the same thing as democratic socialism.

Welfare statism wants all the wealth and advantages that laissez-faire and private property creates, but at the same time, it wants to undermine the very things that makes all that wealth possible. Welfare statism takes for granted the advantages of laissez-faire — it wants to hold power over the producers of wealth — yet it wants those same wealth-producers to keep producing it for them. It is a short-sighted ideology the prevalence of which dominates academia from sea to shining sea.

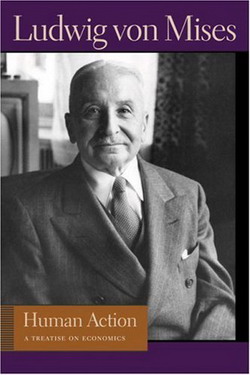

The welfare state, which is what we live in today and have for some time, is the result of what Ludwig von Mises called the “hampered or mixed market economy.” It is not identical to socialism proper, primarily because it is not explicit enough, but it too is a variation on the same theme.

Remember clear back in 2013, when many mainstream dems were citing Venezuela as a model to emulate — “an economic miracle,” as David Sirota called it, created by Hugo Chavez’s “full-throated advocacy of socialism.”

(A number of the left-wing geniuses in this country meanwhile took private jets down to Venezuela to pay their respects to the man himself.)

Have you, incidentally, ever seen the inside of a Venezuelan supermarket?

Let us not (ever) forget either that time Bernie Sanders — who owns three mansions — was lecturing us that “the American dream is more apt to be realized in Venezuela…. Who’s the banana republic now?”

He asked this ostensibly in all seriousness.

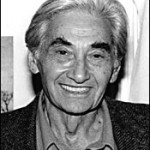

In response to which, Robert Tracinski wrote:

We’re seeing the answer to that. Today, Venezuelans are starving and the remainders of the Chavez regime are sending gangs of armed thugs into the streets to attack anyone who protests. And all of the people who praised the Venezuelan regime as a paragon of socialism? They suddenly don’t want to talk about it….

The bodies keep piling up, but the ideology that produced those bodies always gets a free pass. You know what this is? It’s the equivalent of Holocaust denial for the Left.

There has long been a ritual, which I sincerely hope will continue, in which young people are required to immerse themselves in the horrors of the Holocaust. But our culture never did that for the horrors of socialism, which is how you get a majority of young people having a positive view of socialism.

What have they missed that they can believe that? Here’s what they’ve missed: the artificial famine in Ukraine, the Soviet Gulags, the forced deportation of Lithuanians, the persecution of Christians, China’s Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution, the killing fields of Cambodia, North Korea’s horrific prison camps and famines, the systematic impoverishment of Cuba, and now Venezuela’s collapse into starvation and mass-murder. All of this should be absolutely required background knowledge for any educated person.

I didn’t provide links for the second half of those examples. If you don’t know them, your assignment is to go look them up, because you’re precisely the sort of person who needs to learn about them.

Now when I cite all of this history, there’s always someone who insists that it isn’t fair to pin all of these crimes on “socialism” because those examples weren’t really socialism. The only “real” socialism is the warm, fuzzy welfare-statism of a handful of innucuous Western European countries. This is a pretty obvious version of the No True Scotsman fallacy, and a good way of disavowing responsibility for the disastrous results of a system you praised just a few years earlier.

The real question is this:

When will left-wingers and right-wingers alike realize that the principle underpinning this entire godforsaken political ideology — i.e. the belief that it’s okay to force people to live for one another — is as dangerous and as dogmatic as any religion … and for the exact same reasons: they’re both predicated upon a policy of pure, unadulterated blind belief.