The following is from a good article, published earlier today and penned by Edward Peter Stringham, an economist I much admire. Here’s an excerpt:

Hundreds of professors associated with Yale University organized a letter with signatures to send to the White House. It was signed by 800 credentialed professionals largely from the fields of epidemiology and medicine. It is not what I would call a free-market treatise, to be sure, and I do not agree with parts of it.

Still … the letter warns that the crackdowns, shutdowns, travel restrictions, sweeping closures, and work restrictions could be counterproductive and not produce the results people hope for. This echoes the concern expressed by Stanford epidemiologist John Ioannidis and his recently published work that warns that we are taking extreme measures with low-quality information with little interest in costs.

And where the letter worries about the loss of public services, I would add the worry of the loss of essential economic services. I will quote large sections of this letter. My main message here is as follows. If you worry that the coercive measures government is using and proposing go way too far, you are not alone: many in the mainstream of the medical profession agree with you.

“Mandatory quarantine, regional lockdowns, and travel bans have been used to address the risk of COVID-19 in the US and abroad. But they are difficult to implement, can undermine public trust, have large societal costs and, importantly, disproportionately affect the most vulnerable segments in our communities. Such measures can be effective only under specific circumstances. All such measures must be guided by science, with appropriate protection of the rights of those impacted. Infringements on liberties need to be proportional to the risk presented by those affected, scientifically sound, transparent to the public, least restrictive means to protect public health, and regularly revisited to ensure that they are still needed as the epidemic evolves.

“Voluntary self-isolation measures are more likely to induce cooperation and protect public trust than coercive measures, and are more likely to prevent attempts to avoid contact with the healthcare system.”

Read the full article here.

I also recommend A Virus Worse Than the One from Wuhan, also by an economist (and historian) named Lawrence W. Reed, of the Foundation for Economic Education.

But I list the best one last, and I highly recommend this piece — written by a man who, like me, classifies himself not as a “libertarian” (whatever that actually means) but as a classic liberal. It reads, in part:

It’s no surprise to see the headline, “There Are No Libertarians in an Epidemic.” By “libertarians,” the author means advocates of small government and individual liberty.

The idea is that when a crisis hits, everyone suddenly realizes how much they need a bigger government. This is a bizarre argument to make about a virus that got a foothold partly because of the corrupt and tyrannical policies of a communist government in China. The outbreak is currently at its worst in Italy, where socialized medicine has not turned out to be a panacea. And it was allowed to get out of control in America because the feds imposed an incompetent government monopoly on COVID-19 testing, blocking the use of better and faster tests developed by private companies.

Not only has Big Government been a significant magnifier of this crisis, the actual remediating solutions have been largely implemented through voluntary action.

(Link)

Give special notice to that last thing. Because not only is it true: it hits precisely upon an important principle — a foundational principle, and one I’ve been thinking a lot about lately — often lost in the details and often ignored, and that principle is this:

Those of us who believe that “that government governs best which governs least” (Henry David Thoreau, though it’s often misattributed to Thomas Jefferson) are not categorically opposed to any number of the same ideas and ends that the opposite view holds. The distinction is a distinction of means. The crucial issue in question — and I ask you to please consider this — is the issue of forced action versus voluntary action.

Laissez faire explicitly prohibits the initiation of force — which includes government force, as well as force instigated by any individual: government-forced charity, for example, and all variations thereupon. But this does not mean that people can’t organize and act voluntarily to achieve socialistic ends. In fact, one of the most persuasive arguments — certainly for me when, as teenager, I began looking more deeply into these sorts of subjects — is the overwhelming success of voluntary charities and safety nets, which almost invariably work more efficiently and effectively than systems of legal compulsion and state-sanctioned force (like housing projects and Native American Reservations, to say nothing of the bankrupt Medicare/Medicaid systems), as well as the attendant mazes of bureaucracy that these systems necessarily require.

As Lawrence W. Reed wrote in the above-cited article:

Nothing prevents socialists from doing any of these things by voluntary agreement amongst themselves. That’s one of the great advantages of [laissez faire]: You and your willing friends can practice socialism if you so desire, whereas a great disadvantage of socialism is that you can’t practice full freedom until socialism fails so miserably that even its sycophants throw in the towel.

But a safe bet is that in a world of some eight billion people, not a single socialist will make the slightest attempt to do any of these things. The whole idea of socialism—which explains the inherent hypocrisy of its advocates—is not to freely practice what you preach. It’s to use power to force others to practice what you preach.

He’s right: under a system of legally guaranteed and fully protected individual rights, which of course includes full property rights, you are perfectly free to practice socialism, as many people in this country have. And yet the opposite of that is not the case.

Nobody has the moral right to seek his own advantage by force. That is the one unalterable, inviolable condition of a true society. Whether we are many, or whether we are few, we must learn only to use the weapons of reason, discussion, and persuasion…. As long as hummans are willing to make use of force for their own ends, or to make use of fraud, which is only force in disguise, wearing a mask, and evading our consent, just as force with violence openly disregards it — so long we must use force to restrain force. That is the one and only one right employment of force … force in the defense of the plain simple rights of property, public or private, in a world, of all the rights of self-ownership — force used defensively against force used aggressively (Auberon Herbert, The Principles of Voluntaryism, 1897).

And the wise and erudite Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835), ahead of his time and timeless:

Any State interference in private affairs, where there is no immediate reference to violence done to individual rights, should be absolutely condemned.

Moral law obliges us to regard every individual human being as an end to him or heself.

Political activity can only extend its influence to such actions as imply a direct trespass on the rights of others.

It is only actual violations of right which require any other power to counteract them than that which every individual possesses.

The State organism is merely a subordinate means, to which individual person, the true end, is never to be sacrificed.

The State, then, is not to concern itself in any way with the positive welfare of its citizens … except where these are imperiled by the actions of others, but it is to keep a vigilant eye on their security.

Actions do no violence to right except when they deprive another of a part of his freedom or possessions without, or against, his will.

(Wilhelm von Humboldt, The Limits of State Action)

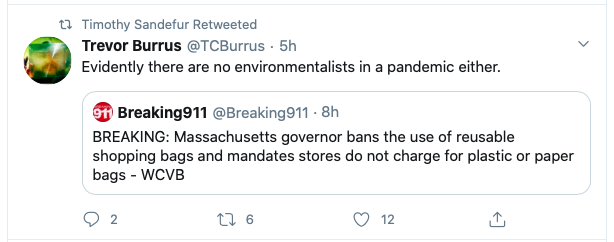

2 Replies to “800 Medical Specialists Caution Against Draconian Measures & There Are Evidently No Environmentalists In A Pandemic Either”