MNSBC host and self-described “Democratic political strategist” Krystal Ball was recently discussing Thomas Piketty’s latest book — the subject of which is income inequality — when she foolishly introduced into her dithyrabmic George Orwell’s famous book Animal Farm.

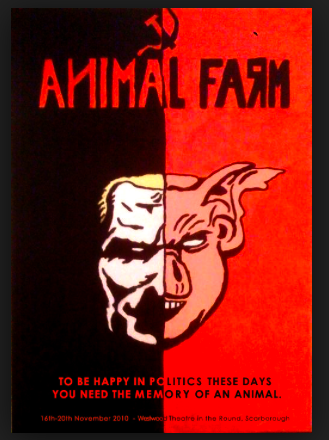

“Even the august and ostensibly economically literate Wall Street Journal tells [Piketty] to read Animal Farm,” Krystal Ball said. “Animal Farm, hmm. Isn’t that Orwell’s political parable of farm animals where a bunch of pigs hog up all the economic resources, tell the animals they need the food because they’re the makers and then scare up a prospect of a phony boogie man every time their greed is challenged?”

No, it is not.

George Orwell was a soft socialist all his adult life and did not believe in laissez-faire, but that hardly means Animal Farm is an anti-capitalist novel. Even the most liberal reading of Animal Farm could not possibly conclude that it’s anything other than an indictment — an utter indictment — of Soviet Russia and totalitarianism in general, which, incidentally, was what George Orwell himself said:

“Of course I intended it primarily as a satire on the Russian revolution” (source).

For those of you who haven’t read Animal Farm, every significant scene apes an actual event from Soviet history — including the Bolshevik Revolution, Trotsky fleeing the country, and Joseph Stalin’s Obama–like cult of personality.

As CJ Ciaramella recently put it:

“At the end of the book the once-egalitarian farm has devolved into a dictatorship where the animals toil harder, longer, and for less food than they did under the yoke of human masters before the revolution.

“So Animal Farm might be the worst analogy for the problems of late capitalism. A better example might be that our system has produced someone with the critical reading skills of a potato, and then allowed her to rise to the position of a national TV news host, mostly by virtue of her membership in the entrenched political class.”

(Link)

Back to the books, Krystal Ball.