On this day in 1776, America’s thirteen colonies broke away from Britain to forge a new nation free to govern itself. The guiding principle behind this new nation is stated very clearly in America’s foundation document — the Declaration of Independence — which says that all human beings by nature possess the unalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and that governments are instituted among humans to protect these rights.

On this day in 1776, America’s thirteen colonies broke away from Britain to forge a new nation free to govern itself. The guiding principle behind this new nation is stated very clearly in America’s foundation document — the Declaration of Independence — which says that all human beings by nature possess the unalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and that governments are instituted among humans to protect these rights.

I emphasize the word protect in this context because it was (and in many ways still is) a revolutionary idea: for in most lands, including America today, government is looked upon as a sovereign ruler of the people. But this was not America’s original intent.

The word unalienable means “that which cannot be transferred, revoked, or made alien” — and everything that has made America great is merely an elaboration upon this foundational principle.

The Declaration of Independence is not a treatise on political theory but a statement to the world of what the founders of America believed to be a self-evident truth: namely, that we each own ourselves and our property in full.

The language used in the Declaration of Independence owes much to John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government, which states that the major function of government is to protect the life, liberty, and property of each person.

The framers of the Constitution indeed believed the legitimate functions of government to be merely protective, and not paternal. As Thomas Jefferson said, “The legitimate functions of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others.”

In fact, politically speaking, those two things are at root the only possible alternatives: protective government or paternal government. (Even anarchy devolves eventually into a de facto government of one or the other of these two.)

America is for this reason a nation of laws: laws which specifically protect “against the instigation of aggression,” for it is ultimately only through aggression, or its threat, that the right to life and property can be infringed or abrogated.

The right to life, which is the fundamental right, is what makes America politically free.

The right to property, which is the only manifestation of the right to life, is what makes America economically capitalistic.

Capitalism is the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness applied to economics.

Capitalism is the freedom to produce and to trade property.

It is of inestimable significance that of the many grievances listed in the Declaration of Independence, a number of those grievances are economic.

Money is property, and private property is the crux of freedom.

Property is subsumed under the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness: obviously, you cannot possess the right to life, liberty, or the pursuit of happiness if you do not first possess the right to produce, keep, and dispose of those things which maintain your life and make you happy.

In this sense, America is correctly known as a country of negative rights.

What that term refers to is the fact that your freedom imposes no burdens and no responsibilities upon any other person except responsibilities of a negative type: you must refrain from violating the same rights in others.

Your rights, my rights, everyone’s rights stop where another’s begin.

Rights are in this way compossible – which means: they can’t conflict since everyone possesses the exact same rights: specifically, the right to one’s own life and property – and only one’s own life and property.

Negative rights are the only possible way for each and every individual, regardless of race, sex, sexual orientation, color, class, or creed, to live freely.

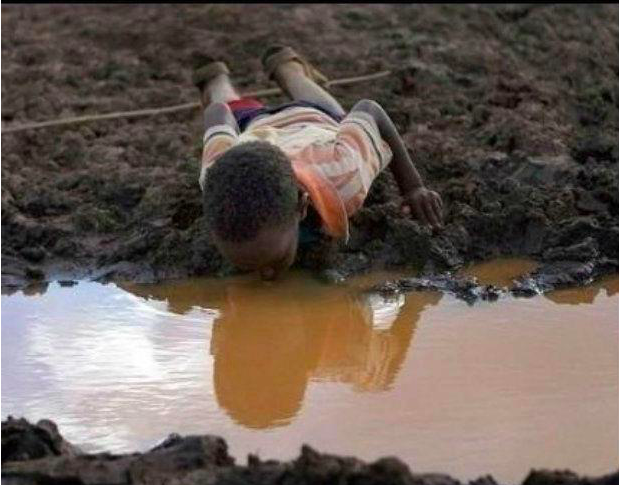

Negative rights do not guarantee a set income. They do not guarantee healthcare. They do not guarantee a level playing field or a level training field. They do not even guarantee success or happiness.

They guarantee only that you are free to pursue success and happiness, and that if you achieve these things, they are yours unalienably. Which is to say, these things cannot be revoked or transferred.

That is the premise America was founded upon.

In other words, negative rights guarantee you the one thing most important to human life: the freedom to pursue your values. In America as she was originally intended, you are free to make of yourself whatever you can, provided you do not infringe upon the same rights in others.

The long war upon the principle of negative rights, which began before the ink was finished drying on the Declaration of Independence, is waged almost exclusively by those who, in one form or another, seek to replace negative rights with so-called positive rights.

Positive rights do not actually exist.

In fact, they’re a complete negation of rights and a contradiction in terms, since by definition positive rights are not compossible – which is to say that in order to be carried out, positive rights require the infringement of the rights of others. So that if, for example, whether or not you work, you possess (which in reality you do not) the positive right to a certain fixed income, it will necessarily require that someone (i.e. the government) takes money from someone else and gives that money to you, in order to provide you with your fixed income. The most obvious problem with this is that no one has the right to take money from any other person; for if someone did possess such a right, from whom would it derive?

Money and all other property may be lawfully taken only by permission.

Permissions are not rights.

Such is the nature of positive rights, whose fatal flaw is built into the very idea of positive rights.

This 4th of July, then, let us celebrate the principle that birthed the greatest civilization in world history: the principle of negative rights.

Happy 4th.