This recent tweet captures the half-assed distinction Marx tried to make between so-called bourgeois property and personal property:

On the thirtieth anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre — when the totalitarian socialist government of China quashed, with extreme force, a political uprising by the people of China who rebelled at last against the obliteration of their freedom — I sincerely hope that the dire error of the illustration above is both obvious and horrifying.

If, however, it’s not obvious or horrifying, this is perhaps a testament to the steady erosion and the subsequent non-understanding of the concept of rights — which, in turn, is the result of the ideology and the ideas which have for decades reigned supreme in academia and across western culture.

The fatal error in the illustration above is this:

A complete non-understanding of — or, worse, deliberately ignoring — the supreme importance of the amount of money (i.e. capital) that it takes to start and run a large business, including but not limited to all the equipment required; and even more important than that: the role of ideas and the knowledge and learning that goes into starting and maintaining a business.

James Jerome Hill, Thomas Edison, John Rockefeller, Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Sam Walton, Ray Crock, and thousands upon thousands upon thousands of others could be appropriately cited here — and they should be: because they represent the principle precisely: they and all others like them, who have brought the entire world incalculable amounts in incalculable ways, are the total argument to the illustration above. Moreover, any employee of any business is free to raise her or his own capital and invest her or his own time and learning into a business of her or his own, and the division of labor and the specialization which creates the machines that the business-owner buys with the capital she’s raised is perfectly legitimate, and it is good.

But I suggest we make it more personal:

Let us say your mother, who was born into poverty, the second oldest in a family of ten, and who then worked very hard all her life, beginning as a young teenager, in restaurants and kitchens around southwestern Colorado — let us say that one day this mother of yours, after 53 years of working and learning her trade, of perfecting her pie-crusts and cinnamon rolls and donuts and biscuits and all the other recipes she learned and developed and invented, finally went for it: She mortgaged the home she did not yet fully own, and she raised other money, and she at last, at age 54, opened her own restaurant.

She thereafter worked tirelessly to make this restaurant succeed — and it did: People voluntarily and happily came into her establishment and paid their money to eat her pies and cinnamon rolls and donuts and biscuits and soups and everything else she’d learn to make and create, and which she daily worked so hard in producing anew. In turn, your mother, because her business was earning money, could afford to hire people — people who voluntarily agreed to work for her in exchange for a wage, and whom she taught the things she’d learned over the course of her life. And more than that: these employees liked your mother — they liked working for her, because she was fair, and they learned from her as she learned from them, and the money was good for everyone. The contractual relationship was mutually beneficial: because she hired them and they voluntarily agreed upon the wage she offered, and because the restaurant, which (let us never forget) was her idea and upon which she took all the financial risk and started up, and, armed with knowledge she’d accumulated and developed over four decades of her life, she worked tirelessly to build — knowledge and skill people willingly paid for — she succeeded.

Now imagine someone suddenly comes along and tells your mother that the employees who voluntarily agreed to work for her, and who do so by contractual arrangement, and who invested no capital in starting up this restaurant or buying any of the expensive equipment, and who can leave at any time — they by right have equal ownership in your mother’s business, merely by virtue of the fact that she hired them.

That is the horrifying error in the illustration above.

The exact same principle applies to any business, no matter the specific industry.

If you think that I’m in any way being hyperbolic, you’re perhaps forgetting your history lessons.

It’s called expropriation. It is a horrible injustice — and it’s flatly, unequivocally wrong.

It’s what everyone from Lenin, to Mao, to Castro, to Pol Pot, to Che, to Occupy Wall-Street, to many others, believe:

Note the phrase “by force.” Under a system of freedom, anyone is allowed to create a business which is non-hierarchical and entirely employee-owned. Under the opposite system, however, the opposite thing is not true.

It is a very great irony indeed that socialism — which through the media-mob and especially the social-media-mob — has, in the last two decades especially, developed a reputation as being hip and trendy and young and even new and cool: a glittering new idea, this 21st century socialism. The irony is that it’s just the opposite, and the grim joke is on all the true-believers: because the ideas which underpin all socialist theory are embarrassingly outdated, antiquated, and old as hell. They’re also proven failures, mathematically doomed.

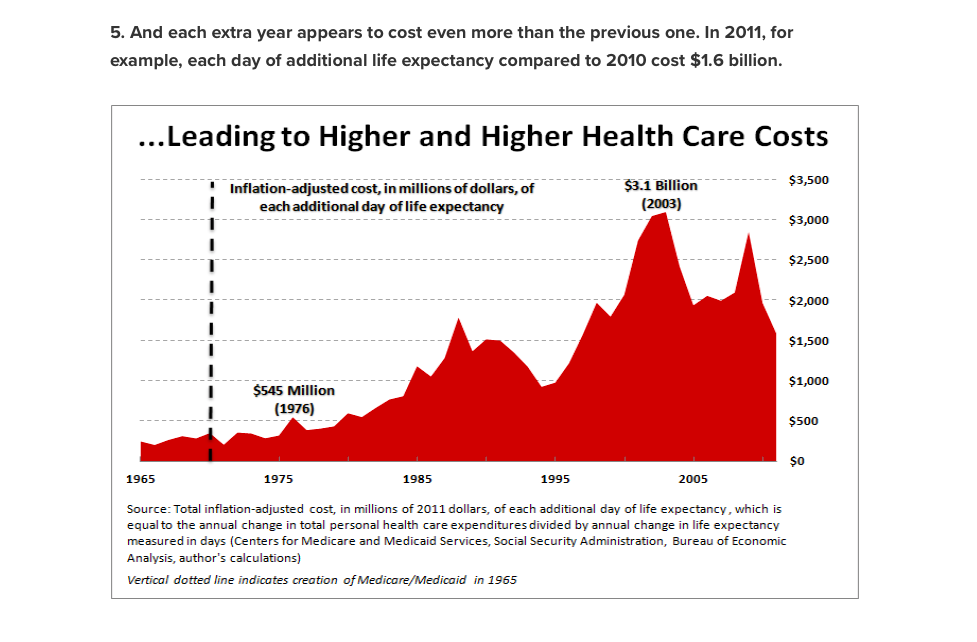

Not only are these ideas out-of-date, in fact: they’re out-of-touch — out-of-touch with even the most rudimentary economic laws — and it is a frightening thing when the leaders of the free world, behind whom the people have lined up in lockstep, do not have any inkling of these rudimentary laws (such as knowing that America absorbs and subsidizes much of the world’s socialized pharmaceuticals).

You have the natural-born right to grow wealthy, so long as you do not infringe upon the rights of others: your rights, my rights, everyone’s rights stop where another’s begin.

If you need any more convincing, please watch the following debate — it’s genuinely fascinating — in which the young, hip socialist (founder of Jacobin Magazine) is soundly defeated by a so-so defender of private-property and free-exchange. I urge you to take particular note of the young socialist’s absolute refusal to answer the question: if people voluntarily want to work for someone who starts up a business, and if these same people voluntarily agree to that business-owner’s offered wage, should they be free to do so? Should such business transactions be legal and allowed?

And the reason the hip socialist does not answer this question is that he doesn’t believe this business structure and this sort of voluntary transaction should be allowed — because he, like so many others, has bought into the dismally old and failed ideology of egalitarianism-by-force.