Political theory is the theory of government. It is a sub-branch of ethics, and economics, in turn, is a sub-branch of politics.

Political theory is the theory of government. It is a sub-branch of ethics, and economics, in turn, is a sub-branch of politics.

Ethics — the science of human action — precedes politics because politics is the science of human action in societies, and societies are composed only of individuals. For this reason, the individual has hierarchical primacy.

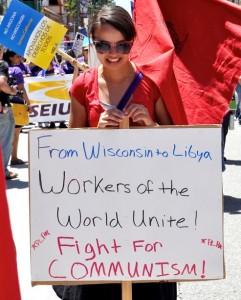

Capitalism, socialism, communism, anarchy — these are all a species of the genus ethics, as is any specific political theory.

Governments, properly defined, are the body politic that have the power to make and implement the laws of the land, and humans are the only species who possess them. But what ultimately gives rise to these political bodies, and do we really need them at all? If so, why?

Some 40,000 years ago, when Homo sapiens sapiens first emerged, we existed exclusively in bands and small tribes.

A band is the smallest of societies, consisting of five to seventy-five people, all of whom are related either by birth or marriage.

Tribes, the next size up, consist of hundreds of people, not all of whom are related, although everyone is known by everyone else.

It is for this reason that conflicts in band and tribal life are resolved without the need of government. Indeed, it’s a well-established fact among anthropologists that governments do not exist in societies of this size.

As Jared Diamond appositely explains it in his otherwise overrated Guns, Germs, and Steel:

“Those ties of relationships binding all tribal members make police, laws, and other conflict-resolving institutions of larger societies unnecessary, since any two villagers getting into an argument will share kin, who apply pressure on them to keep it from becoming violent.”

Homo sapiens lived for approximately 40,000 years in just such non-governmental societies.

Around 5,500 BC, however, chiefdoms arose.

Chiefdoms are one size up from tribes but still smaller than nations.

These societies have populations that number in the thousands or even tens of thousands, whereas nations consist of fifty thousand people or more.

It is at the stage of chiefdoms that the necessity of government begins; for when populations increase to this size, the potential for conflict and disorder increases proportionally.

And here we get a glimpse of government’s primary function: to protect against conflict.

As long as the potential for conflict exists among humans, the need for protection and adjudication exists as well.

“With the rise of chiefdoms around 7,500 years ago, people had to learn, for the first time in history, how to encounter strangers regularly without attempting to kill them…. Part of the solution to that problem was for one person, the chief, to exercise a monopoly on the right to use force” (Ibid, p. 273).

The legal use of force is the defining characteristic of government.

It is also the fundamental difference between governmental action and private action.

In the words of Auberon Herbert, speaking over 100 years ago:

Nobody has the moral right to seek his own advantage by force. That is the one unalterable, inviolable condition of a true society. Whether we are many, or whether we are few, we must learn only to use the weapons of reason, discussion, and persuasion…. As long as men are willing to make use of force for their own ends, or to make use of fraud, which is only force in disguise, wearing a mask, and evading our consent, just as force with violence openly disregards it – so long we must use force to restrain force. That is the one and only one right employment of force … force in the defense of the plain simple rights of property, public or private, in a world, of all the rights of self-ownership – force used defensively against force used aggressively (Auberon Herbert, The Principles of Voluntaryism, 1897).

Among individuals, the initiation of force is illegal, whether the force is directly used, as in rape, or indirectly used, as in extortion (a crucial distinction, incidentally, which Mr. Herbert notes in his fraud-is-force-in-disguise example above).

People can only infringe upon the rights of other people by means of (direct or indirect) force.

In this sense, government is an institution whose function is to protect the individual against the initiation of force.

In the words of Thomas Jefferson: “The legitimate functions of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others” (Notes on the State of Virginia).

Around the same time that Thomas Jefferson was writing those words, another articulate fellow by the name of Wilhelm von Humboldt independently came to an almost identical conclusion:

Any State interference in private affairs, where there is no reference to violence done to individual rights, should be absolutely condemned…. To provide for the security of its citizens, the state must prohibit or restrict such actions, relating directly to the agents only, as imply in their consequences the infringement of others’ rights, or encroach on their freedom of property without their consent or against their will…. Beyond this every limitation of personal freedom lies outside the limits of state action (Wilhelm von Humboldt, The Limits of State Action, 1791).

What professor Jared Diamond incorrectly refers to as government’s “right to use force” (governments do not, strictly speaking, possess rights but only permissions) is a sentiment that has been stated more succinctly many times by Enlightenment thinkers, such as the best theoreticians among our Constitutional framers; but it was perhaps expressed most eloquently by the fiery political philosopher Isabel Paterson:

Government is solely an instrument or mechanism of appropriation, prohibition, compulsion, and extinction; in the nature of things it can be nothing else, and can operate to no other end…. Seen in this light, government is so horrific – and its actual operations in the past have been so horrible at times – that there is some excuse for a failure to realize its necessity (Isabel Paterson, The God of the Machine, 1943).

If, however, government only becomes necessary when societies reach the size of chiefdoms or beyond, what precipitated this sudden population leap, when for 40,000 years — by far the majority of our short history — human growth had remained relatively static?

Why, in other words, do we not still exist in bands and tribes, without the need of government?

The answer, it turns out, is food.

“We have seen that large or dense populations arise only under conditions of food production.… All states nourish their citizens by means of food production” (Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel).

When survival is made easier, populations increase. When populations increase, societies become more complex. When food production increases, mankind increases, societies become increasingly complex, and governments become necessary to maintain order. So it is with increased food production that the science of economics is born.

At root, economics is indeed the science of production and exchange.

Money, in the form of currency, is nothing more, or less, than a symbol of production — an invaluable one, to be sure, since money simplifies so drastically the process of exchange.

It also creates the possibility to store and save over long time periods and makes usury possible, which in turn creates more wealth. This is a crux because it illustrates the deep connection between politics and economics.

Thus, increased food production equals increased population equals increased production equals more people equals more societal complexity, and so on, reciprocally.

This is the process whereby societies develop the need for government.

This is why the fact of government is inescapable.

Whatever a society’s original size, smaller ones only make that initial leap to larger by producing more food.

(If they don’t make it, they are absorbed either by the actual use of force or by its mere threat, by the societies that do produce more food. For this reason, bands and tribes have become all but obsolete today, with a few Amazonian and New Guinean exceptions, most of which are also being swiftly amalgamated.)

Thereafter, in order for that society to flourish, it must now continue to produce food, but it must also efficiently manage its size increase, with all that ensuing complexity. Countless societies have foundered at this stage, as they still do today (see, for example, present day Yugoslavia, or Turkey, or Russia).

Advancements in irrigation, the domestication of animals, the introduction of fertilizers and pesticides, these things begin to make societies complex, because they increase food production. But with this added complexity come new challenges:

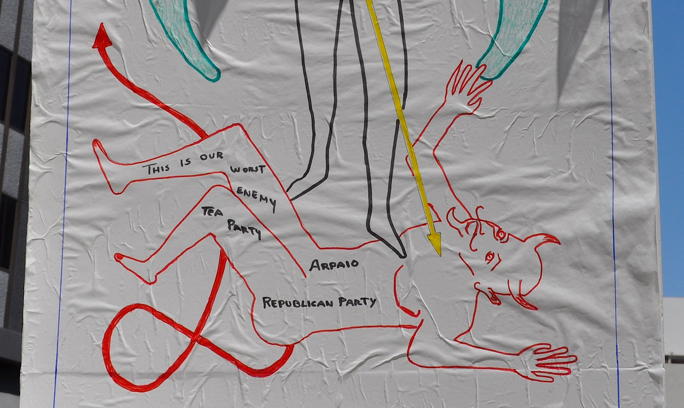

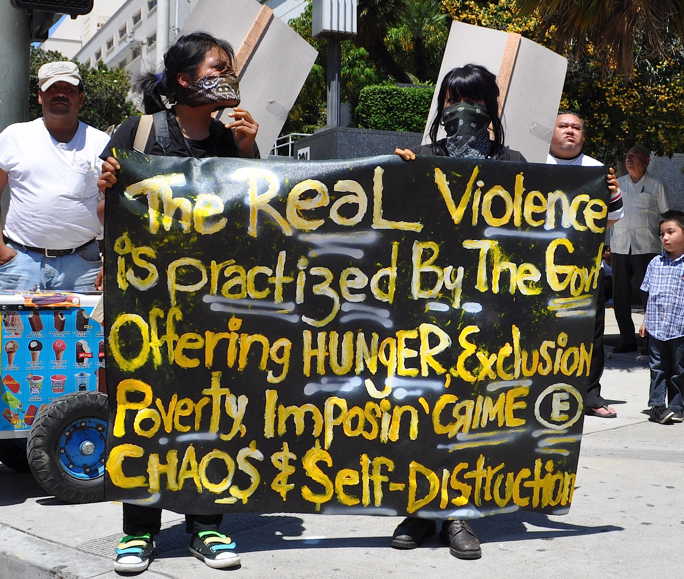

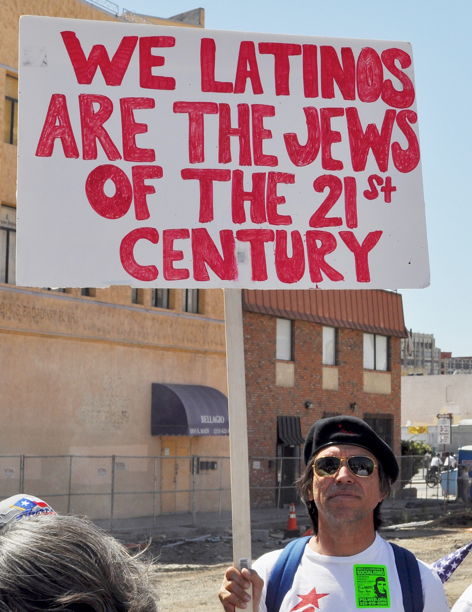

To thrive, these societies must sort out and solve a host of additional problems, ranging from mass uprisings, to increasing economic developments, to internecine warfare, to the threat of governmental takeovers, to crime and punishment, to many, many other things as well.

In the final analysis, then, we can say that governments are unique to humans because humans are the only conceptual species. We produce our food, we build our homes, we create our medicine, we extract our energy, and we deal with one another not as animals, by brute force, but as humans, by agreement.

Trade is the natural drive of the conceptual mind.

So that at this point, our world without government would collapse into chaos — until, that is, the strongest faction seized control, forcefully, you can be sure, and then laid down its own version of order (see present day Somalia).

Who would stop them?

Other warring factions?

In the end, however necessary government may be, please never forget this:

“In its best state, government is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one” (Thomas Paine, Common Sense).

“Government is not reason, it is not eloquence — it is force. Government is like fire, a dangerous servant and a fearful master.”

Government, in short, is inherently dangerous because it holds exclusive power over the people.

The task, then, is not necessarily to do away with government altogether but rather to limit government in the extreme: to build a government which protects its citizens without, at the same time, creating oppression of any kind, including taxation to the point of plunder under that mythical guise of a “right” to redistribute your money – which is the symbol of your work.