For about ten years now, every time the owner of some platform or another decides, for whatever reason, to change its terms, you’ll almost immediately hear a wild outcry for “justice,” followed by a backlash against “robbing people of their livelihood,” and then there often begins the predictable protests against “late-stage capitalism” and “unregulated markets” and “disempowerment.” Et cetera.

(Please note and remember: nowhere have markets ever been completely unregulated, and they most certainly are not today.)

This phenomena happened with Google.

This happened with YouTube.

This happened with Bing.

This happened with Facebook.

This happened with Patreon.

This happened with Tumblr.

This happened with Reddit and confounded people with college educations.

This happened with Instagram and confused Erika Lust, the porn director mentioned below.

This happened with many, many other companies, some of which (and there is a clue here) went out of business for the decisions they made, and it will continue to happen.

Yesterday, it happened (again) with PayPal, so that as of yesterday PayPal now no longer “partners with” PornHub.

Very big deal, I know. And yet to judge from the outcry, you’d think it was armageddon.

PayPal’s decision may or may not have had something to do with the recent and horrifying story which hit headlines October 30th.

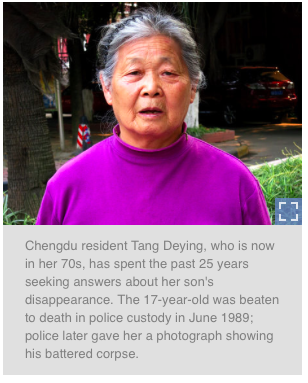

This story concerns a 15-year-old girl who’d been missing for a year and who was then spotted in 58 videos which had been uploaded to Pornhub — as well as Snapchat and Periscope — videos which show the girl, who’d been abducted, being repeatedly raped by her abductor. These videos proved sickeningly popular, and I have a very good idea about why precisely this is, but that’s a subject for a later post.

It is, I’m afraid, time again for me to state the obvious — the obvious and the fundamental — and I admit I find it exceptionally disheartening that such elementary things are so poorly understood:

These are privately owned companies. They can change their terms if they want, and they can change them whenever they want, as you can leave and delete them from your life whenever you want. Users did not use these platforms before they existed, and users do not now suddenly have claim to ownership or a say in how these privately owned companies choose to run their business. Users use these platforms by choice. If these platforms change their terms of service, they are allowed to. Users can write letters and can post as much as they’d like on their own platforms and on any other platforms that allow it, but there is nothing wrong with private companies doing this, and there’s (currently) nothing illegal about it, nor should there ever be. PayPal can choose to do business with Pornhub, or not.

This is not at all a complicated subject. The fact that so many putatively educated people don’t understand something so elementary is a sad testament to the world’s understanding of basic economic principle. You know what it’s like? It’s like a fucking joke to me.

Thanks entirely to social media, a whole new subculture and a whole new generation has recently discovered a term which, for the most part, they did not know anything about even ten years ago. This partially explains why so many among this generation and among this subculture use the old and venerable term as if it were somehow novel and even new.

But in actuality, this term — and, more precisely, the principle behind the term — is something which many have fought tirelessly for for decades and even centuries: fought for in full, I should say, by which I mean, in every aspect of human life.

That term is “decriminalization.”

Decriminalization is similar to deregulation and to legalization, but it is not synonymous.

You’ll be excused, by the way, if you don’t quite recognize the full word — decriminalization — since the term is these days most often used in truncated form, presumably to fit character-count and the trendy terminology of social-media speak: decrim.

Today, the overwhelming majority of people whom you’ll hear discussing decrim are referring to one and only one industry, and that industry is not, unfortunately, the healthcare industry with all its licensing-law monopolies and mandatory health-insurance laws and so forth.

Nor is it unfortunately in reference to zoning laws.

It is not in context of nationalizing and socializing and subsidizing any of the many arms of agriculture, nor any of its offshoot industries, and it’s not about decriminalizing property rights on Native American Indian Reservations.

It also, I regret, has nothing to do with government bailouts of banks or automobile companies, nor does it concern the thousands and thousands of bureaucratic pages added to the Federal Register each year, nor the preposterous gambling laws in America, which are often backed with equal fervor by left-wingers and right-wingers alike.

It’s not about decriminalizing those who don’t comply with mandatory solar-panel laws, or any other mandatory “renewable energy” laws, and it has nothing to do with emissions and the sheer stupidity of officially labeling CO2 (one of the building blocks of life) a “pollutant.”

Neither does it have anything to do with decriminalizing the building of new nuclear reactors, nor to hydraulic fracturing decrim, nor to decriminalizing waste-disposal — specifically by abolishing any and all mandatory recycling laws, which mandatory laws have generated astronomically more pollution and waste.

It’s not about decriminalizing our absurd drinking-age laws, which so many countries in the world do not have — to no detriment whatsoever — and it’s not any decrim related to drugs or alcohol or tobacco or firearms or firecrackers or compulsory education or military conscription or progressive taxation or mandatory licensing laws for any number of other industries, or anything like this. Nor is it about decriminalizing all marriage, so that this institution is separated from the state entirely. Neither is it about any and all forms of coercive welfare, including but certainly not limited to all publicly funded, non-voluntary healthcare subsidization. (You may, of course, voluntarily subsidize any form of welfare-pool or “safety net” you’d like, as was once the case, should anybody choose to organize one, instead of relying upon government compulsion to do it.)

Nor, I very much regret, is it about decrim of all interstate trade and all international trade by abolishing all trade tariffs and all prohibitions against such trade.

Today, rather, decrim is used almost exclusively in the context of the sex industry.

I, along with many others who advocate full unadulterated laissez-faire, have fought long for the total decriminalization of all voluntary trade and consensual transactions, which of course includes drugs, sex, rock-and-roll, gambling, et al, and I have done so for a very long time, and I’m on written record as having done so, and over this subject I’ve lost many people whom I thought were friends. My convictions remain.

When, however, any industry, no matter what that industry is, explicitly pedals pedophilia and rape and other atrocity exhibitions, it falls squarely within the proper jurisdiction of the law. This of course goes without saying, though perhaps not for some.

I am not, for the record, talking about the depiction of non-consensual strangulation and other acts of extreme violence (including snuff), unspeakably disgusting as I find it, which depictions of violence are everywhere in porn — so much so, incidentally, that a number of so-called sex-positives (a bullshit term if ever there was one, and I say that primarily because people who coin terms like this are precisely the people who can’t conceive that there are humans who are completely positive about sex, to the point of loving it — yes — who are open and experimental and not phobic in the least, and yet who nonetheless abhor violence and phoniness and, in addition to that, and more importantly, actually like to spend time thinking about and reading about and talking about a great many other things besides sex), such as Dan Savage now saying:

“There’s this normalization of strangulation and other violence during sex — strangulation without asking: one recent survey showed 13% of sexually active girls aged 14 to 17 had been choked nonconsensually.”

Yes, you read that age-range right: 14 years old to 17 years old, and the boys are statedly getting this from the “edgy” porn they watch.

Quoting porn director Erika Lust, who laments nominally — and only nominally — that “face slapping, choking, gagging, and spitting has become the alpha and omega of any porn scene and not just within a BDSM context. These are presented as standard ways to have sex when, in fact, they are niches…. Young people will go to the internet for answers. Many people’s first exposure to sex is hardcore porn. [It teaches children] that violence and degradation is standard.” (Niche? Hardcore? Violent? Degrading? But I regard “face slapping, choking, gagging, and spitting” as nonsense boring vanilla shit, strictly for squares. And don’t even get me started on the subject of actual “love” and emotional connection between two human beings who have brains and who delight in each other’s company even apart from sex. But if you lament it, Ms. Lust, one wonders why you yourself simply don’t stop contributing to it as “the standard,” and work instead to keep it, as you say, “niche.” Upon second thought, though, so what? Why not make it the standard? What’s the problem with that? What’s the problem with 14-year-old boys and girls watching mere depictions of extraordinarily violent nonconsensual sex acts, including staged snuff and necrophilia? Where’s the problem? I see none. What’s the problem with making depicted nonconsensual strangulation and any and all other forms of violence and brutality and “degradation,” as you say, standard and non-niche, since everyone knows that fantasy enactments, no matter how bloody and brutal and degrading and disgusting and pathological they may appear [to the prudish and religious, of course], are not real life, and that’s one of the main reasons for porn, isn’t it? And, anyway, sex-positivity forbids drawing any such patriarchal distinctions as “standard and non-standard” — because when you get right down to it, there isn’t a standard, and for a porn director to presume any sort of demarcation-of-standard, especially a white Scandinavian female porn director, is, if I may speak frankly, privileged, non-inclusive, hegemonistic, sexist, and quite possibly even racist.)

Other sex-positives, if you’ll permit me further use of this bullshit terminology, sex-positives who still work in porn, discuss sex-trafficking and the number of scenes that take place without the performer’s consent, and this, if you ever feel like making yourself sick and if you feel like implanting ghastly images inside your brain that you will never expunge, is a topic you may read about for weeks which stretch into months and months. But I don’t recommend it.

Yes, the porn industry would normalize this, just as Erika Lust correctly notes. They would normalize this and much more. Normalizing is a type of desensitization. Escalation of tastes is largely for this reason, particularly among men, commonplace, and this is not — not by any reasonable person of whom I know — denied.

Recently, in fact, the discussion — if it can even be called that — has fixated (to the point of absurdity) upon whether or not sex can be an “addiction,” or is it just “potentially compulsive.”

This is an absolute non-issue. It’s also stupidly basic.

All addictions involve compulsion — all of them — and virtually all pleasurable things are “potentially compulsive,” including something as fundamental as eating food.

Furthermore, some of the most difficult compulsions to treat and overcome are not technically “addictions,” anorexia and gambling being two of the most notorious. (I once had a customer — Dr. Berry, an M.D. in psychiatry, recently retired at the time that I knew him, who’d graduated top of his class from Stanford School of Medicine — tell me that in his decades of professional experience the toughest compulsion to treat “by far” [his words] was not heroin or meth or tobacco or any other drug or substance, but gambling.)

So please let me repeat this: PayPal, like any and every privately owned company, may partner with whomever they voluntarily, consensually fucking choose, and they can withdraw that consent, just as Pornhub can stop accepting credit cards or whatever, and just as they can all change their terms of service, and they can buy-out Venmo if Venmo chooses to sell (which Venmo consensually did), and you or I can start up a new payment-processing company or invent an app that people can download onto their phones and soon not be able to live without, or we can start-up a new porn platform — or all of the above — or whatever other 101 shit.

Note also that to the extent that laissez faire does exist, when a platform enacts a policy which causes users to leave, new businesses and companies are free to start up and fill this newly created void which, in enacting whatever policy, opened up a demand — and that’s exactly what we’ve always seen and will continue to see, until government and its advocates implement protectionism. (The rivers of tears had not finished drying over Patreon’s change-of-terms before a hundred new and better platforms sprung up, almost overnight, to take its place. Meanwhile, we watch Patreon’s popularity gradually but inexorably fade. It’s called Creative Destruction.)

It is worth noting here, as well, if only in passing and in closing, that the overwhelming majority of advocates for sex-industry decrim are leftist-progressive-socialists, who, as strident and hysterical as they are for decrim, would, however, CRIMINALIZE any number of other industries (including, for example, PayPal’s right not to do business with whomever they choose [see also most of the list above]); and this is especially true, I’ve noticed, of the psychologists and pseudo-neuropsychs arguing on behalf of the sex industry (but no other industry) for decrim, all of whom, without a single exception in my personal experience, are economically illiterate — one even going so far as to say that “there are no good billionaires.” (He wrote this on a phone or computer or tablet invented and brought into existence by a billionaire, in the comfort of a first-world society made possible by billionaire wealth, upon a platform created and popularized by a billionaire. But I’m quibbling, I know.)

This encapsulates why this group will never ultimately fully succeed in the cause — a cause I support though not in mere isolation without reference to its underpinnings — never fully, I say, because they don’t understand the principle behind the cause, which is this.