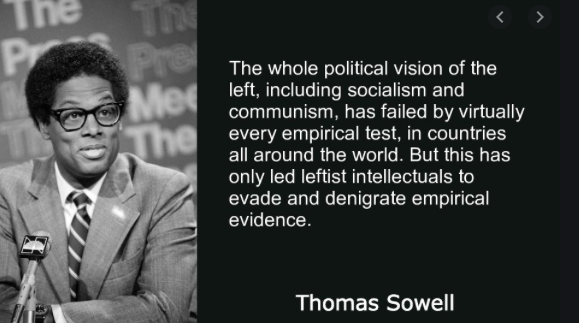

Today is the 90th birthday of the American economist Dr. Thomas Sowell — a true genius and independent-thinker, who’s been an inspiration to me for a long time, and from whom I’ve learned a great deal. I sincerely believe that it has never been more important to read and understand Thomas Sowell.

In his autobiography — A Personal Odyssey — Thomas Sowell writes that as a young student, while getting his economics degrees, he was, like most economists of that time, a devoted Marxist, but that in conducting deep and unflinching studies of the effects of bureaucracy and any number of government interventions, including minimum wage laws, Native American Indian Reservations and the disastrous housing projects, the data led him to an inescapable and overwhelming conclusion: freedom and voluntary exchange promotes prosperity among human beings; governments and their bureaus and their endless taxation schemes do nothing but hamper human prosperity.

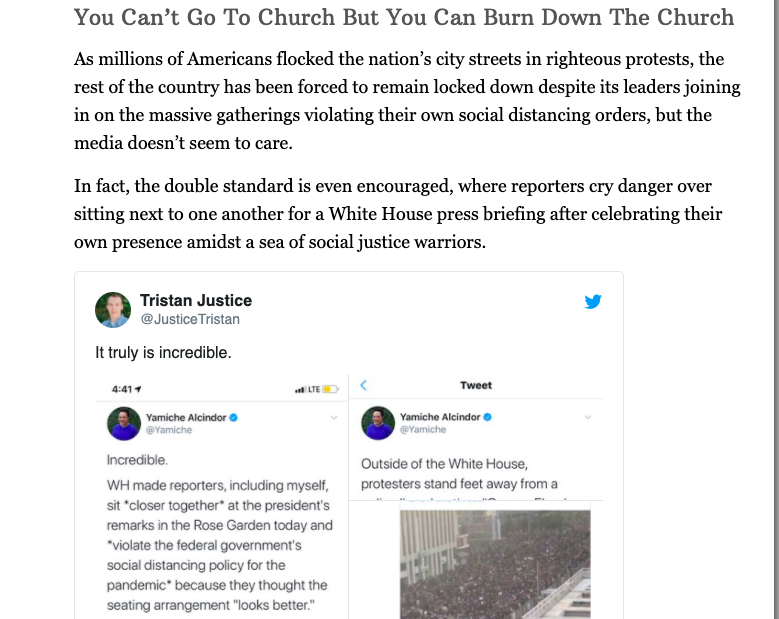

As the economist Richard Eblieng put it:

“Thomas Sowell soon found that the people planning, guiding, and administrating the regulatory and welfare state had self-interested goals and purposes that often had little or nothing to do with actually improving the circumstances of those for whom such legislation supposedly had been passed. Usually very much to the contrary.”

In his book Knowledge and Decisions Thomas Sowell says it this way:

“Historically, freedom is a rare and fragile thing . . . Freedom has cost the blood of millions in obscure places and in historic sites ranging from Gettysburg to the Gulag Archipelago…. That something which costs so much in human lives should be surrendered piecemeal in exchange for rhetoric and vague visions of the future seems grotesque. Freedom is not simply the right of intellectuals to circulate their merchandise. Above all, it is the right of ordinary people to find elbow room for themselves and a refuge from the rampaging presumptions of their ‘betters’.”

On questions of race, racism, rights, justice, so-called social justice and so on, Thomas Sowell and his literature has stood monolithic, an irrefutable force, with reams of hard data which no academic professor of whom I’m aware has ever seriously attempted to refute in full. (Most timely now: Black Rednecks & White Liberals and Discrimination & Disparities.)

Thomas Sowell reminds us over and over how unique America was in its foundational principle — the principle of individual rights: the only country in the history of the world ever explicitly founded on this principle, and which, even when horrifyingly breached at different periods in American history, nevertheless remains the principle that must necessarily be returned to — a self-correcting sort of principle — if, that is, true political-economic freedom for each and every individual is the goal, which for him and for me it is.

In so much of his literature also, he reminds us how justice as that term was originally and constitutionally conceived meant the impartial enforcement of the rule of law, in which the rule of law referred to the protection of individual liberty, private property, and freedom of association and contract, as well as the freedom of each to pursue her or his own individual happiness. The law, in turn, was meant to represent the rules within which free people may voluntarily act and interact, without interference from the government or other criminals and agents of force.

Thomas Sowell disclosed as well, in devastating detail, that in the 20th century the quest for redistributive or “outcome” justice has sought to replace the true conception of justice — saying that most people are, in actuality, not overly concerned in their day-to-day lives with whether “Joe has earned more than Samuel,” as long as there is a general sense that their relative incomes have been acquired honestly and without favors, privileges, and political corruption. It is the self-appointed elites for whom this issue predominantly matters.

Thomas Sowell also documents in detail the horrific consequences which have followed and must inevitably follow when intellectual elites seek to replace individual choice and voluntary exchange with their elitist social-engineering schemes: individual autonomy stripped, private lives transferred to government, voluntary exchange replaced by state coercion, even while more and more political schemes are continuously implemented in the futile attempt to mend the multitude of problems the original schemes created — and all “with little or no thought to the cost in terms of either material standards of living or their impact on the actual human beings who must serve as the manipulated ingredients for these redistributive recipes…. It is this freedom that is being threatened in America and the world in general by those who, like the Bolsheviks of a hundred years ago, continue to claim that everything is permitted to them in the pursuit of making us and our world over into their utopian image of how they think we all should be.”

In Thomas Sowell’s view, the primary problem with the social engineer can be found in the fact that the social engineer wishes to treat people as blank slates upon which the central-planner and her committee can imprint any desired behavioral qualities the said planner deems best. If individual human beings don’t conform to this planner’s preferred forms of behavior, it must mean that evil agents are at work against the government, and governmental force thereby justified.

Perhaps most controversially of all, Thomas Sowell showed in clear and cogent terms that what often passes for “black culture” in the United States, with its particular language, customs, behavioral characteristics, and attitudes toward work and leisure, is in fact a collection of traits adopted from earlier white southern culture.

[Sowell] traces this culture to several generations of mostly Scotsmen and northern Englishmen who migrated to many of the southern American colonies in the 18th century. The outstanding features of this redneck culture, or “cracker” culture as it was called in Great Britain at that time, included “an aversion to work, proneness to violence, neglect of education, sexual promiscuity, improvidence, drunkenness, lack of entrepreneurship, reckless searches for excitement, lively music and dance, and a style of religious oratory marked by rhetoric, unbridled emotions, and abeyant imagery.” It also included “touchy pride, vanity, and boastful self-dramatization….

In spite of racial prejudice and legal discrimination, especially in the southern states, by the middle decades of the 20th century a growing number of black Americans were slowly but surely catching up with white Americans in terms of education, skills, and income. One of the great perversities of the second part of the 20th century, Sowell showed, is that this advancement decelerated following the enactment of the civil-rights laws of the 1960s, with the accompanying affirmative action and emphasis on respecting the “diversity” of black culture. This has delayed the movement of more black Americans into the mainstream under the false belief that “black culture” is somehow distinct and unique, when in reality it is the residue of an earlier failed white culture that retarded the south for almost 200 years (Link).

And — brace yourself — this:

Sowell also says much about how the institution of human bondage is far older than the experience of black enslavement in colonial and then independent America. Indeed, slavery has burdened the human race during all of recorded history and everywhere around the globe. Its origins and practice have had nothing to do with race or racism. Ancient Greeks enslaved other Greeks; Romans enslaved other Europeans; Asians enslaved Asians; and Africans enslaved Africans, just as the Aztecs enslaved other native groups in what we now call Mexico and Central America. Among the most prominent slave traders and slave owners up to our own time have been Arabs, who enslaved Europeans, Africans, and Asians. In fact, while officially banned, it is an open secret that such slavery still exists in a number of Muslim countries in Africa and the Middle East.

Equally ignored, Sowell reminds us, is that it was only in the West that slavery was challenged on philosophical and political grounds, and that antislavery efforts became a mass movement in the 18th and 19th centuries. Slavery was first ended in the European countries, and then Western pressure in the 19th and 20th centuries brought about its demise in most of the rest of the world. But this fact has been downplayed because it does not fit into the politically correct fashions of our time. It is significant that in 1984, on the 150th anniversary of the ending of slavery in the British Empire, there was virtually no celebration of what was a profound historical turning point in bringing this terrible institution to a close around the world (Ibid).

For his lifelong heterodoxy and intransigent independence-of-thought, Thomas Sowell has been smeared by the left — the academics, in particular — as he’s also been vilified, antipathized, demonized, anathematized. Yet his theses have not been refuted or overcome — and for one simple reason above all the others: his ideas are largely right, and the ideas of his enemies are largely wrong.

Because the freedom of each individual — irrespective of race or skin color, sex or gender — is timeless.

On the merits of his arguments and for his articulateness in expressing these arguments — his power to bring complex ideas down to the level of complete comprehensibility — and his accumulation of hard factual data, Thomas Sowell is a total testament to the superiority of individual autonomy, liberty, and voluntary exchange.

On a separate but related note, a man by the name of Kash Lee Kelly — biracial — recently made a remarkable video in which he said the following:

“Black lives matter will come out and start a race war, but they won’t come out and deal with our race.”

Not long ago, The Longevity Project, which studied over 1000 people from youth to death, loosely confirmed, among many other things, what for many seems a fairly obvious truth — namely:

“The groups and people with whom you most closely associate determine the type of person you yourself become.”

I believe Kash Lee Kelly grasps the truth of this — whether explicitly or implicitly — which I also believe is the reason he’s able to articulate so perfectly why he himself does not care to associate with #BlackLivesMatter. This perhaps explains as well how he’s able to see past the tremendous amounts of pressure and hype, the emotional noise, and in spite of it all, spot the Neo-Marixst egalitarian-tribalism of today’s left, which categorically denies the primacy of the individual — specifically, I mean, in grasping how this ideology leads to mindlessness and groupthink.

Protest injustice, yes, protest authoritarianism and racism — protest it at the top of your lungs — any and all forms of it, and I will protest alongside you. But under no circumstances ally yourself with any organization or group which would replace injustice with more injustice — or with a mutated form of the injustice that the protests were initially protesting against.

Do not align yourself with any gang, group, clique, cult, tribe, party, et cetera, which in the name of reparations or anything else, would subordinate one group of individuals to another — and I’m referring here most specifically to the deep and disturbing anti-semitic strain which caused the Women’s March to implode, and the leaders of which, many of them, are now leaders and manifesto-writers for Black Lives Matter:

Know this as well:

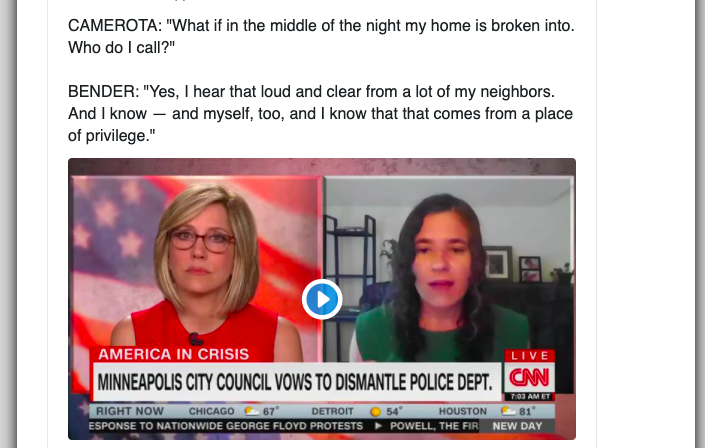

Not wanting to be robbed or raped is not a “privilege.”

Indeed, the whole concept of “privilege” — and I implore you to consider this — has been twisted so tortuously by the postmodern intellectual elites that most people now using this term have replaced the (legitimate) word “rights” with it.

All humans, in other words, have the absolute right not to be raped and robbed — of this I assure you.

To call this a “privilege” is to invite psychological-epistemological chaos — which is to say: it is to confuse thought, since all humans, no matter the race, sex, gender, or any other non-essential, think by means of language. Proper definitions are therefore the first-line of defense against mental disintegration, because in identifying and denoting the essence of what is, proper definitions foster and facilitate understanding, comprehension, apprehension, which is how humans live and prosper.

I can absolutely assure you also that in conflating a “privilege” with a “right,” one is dealing with much more than mere semantics:

This is an epistemic error the ramifications of which are, in the larger context of what gives rise to it, a kind of indoctrination.

“First, confuse the vocabulary.”

Do you think I exaggerate or overstate?

Then don’t read the Seattle rioters’ list of demands — which explicitly call for yet another socialist utopia, believing, like countless socialists before them, that this alone will provide the exultant cure to the dark racist empire’s perilous ills by featuring a new 21st century era of censorship and segregation:

Or this:

Or this:

Or this:

Or this:

Or this:

That provides just a small glimpse into why this strain of today’s leftist ideology will, like the Women’s March (and for the exact same reasons), implode: because it’s philosophically bankrupt.

The collateral damage here will be all the well-meaning people appalled, like so many of us, by blatant brutality — brutality against any individual human being — and who, for lack of a better alternative, aligned themselves with this corrosive ideology, which, you may depend upon it, will not survive, thanks to the overtly racist, tribalistic, anti-individualistic (non)thought-leaders of today’s left.

Thomas Sowell, ninety years young today, is an antidote.